OR WHAT’S A HEAVEN FOR

On The Lost City of Z (2016)

The Immigrant premiered at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival, Gray’s fourth consecutive trip down the Croisette. Afterwards, Gray fell into a depression—a very dark, maybe the darkest and most difficult, period of his life, to the point of struggling with suicidal thoughts.

The main catalyst was that after its world premiere, and then after its American premiere at the 2013 New York Film Festival, the movie was simply.... not released. And for a while it looked like it may never be. This due to the terribly unfortunate, unlucky, and for Gray unavoidable fact that the film had been bought by none other than Harvey Weinstein. Over a decade after their years-long clash over the cut, release, and post-film legal battles accompanying The Yards, Weinstein had acquired another one of Gray’s movies for distribution, now under his new banner of The Weinstein Company. He had acquired distribution rights in June 2012 while the film was in post-production; those who had funded the film told Gray that they were selling the film to Weinstein (who hadn’t even seen the film, but apparently liked what he heard about it)—Gray begged them not to. But to no avail. Lo and behold, when Weinstein finally saw the film he wasn’t satisfied. The film had been completed in time to bow at the 2012 Toronto Film Festival, but Weinstein held it behind his back for next year’s Cannes because he was trying to get Gray to change the ending. (What must have been a sickening occasion of déjà-vu for Gray.) He of course wanted it more upbeat; Weinstein’s cut would have been “88 minutes [with] a Sound of Music-style ending with a soaring camera shot, with Marion and her sister walking over a mountain in LA, narration saying ‘I made it, I made it,’ soaring music, and all that.” But Gray, who at least technically did have final cut, adamantly refused to change his movie; there was no way he was going to let what happened to The Yards happen to this film. As a kind of revenge, one supposes, Weinstein put the movie in a drawer for almost a full year. And when it was finally released in U.S. theatres, on May 16, 2014, it was released with little to no promotion whatsoever.

It was an artist’s worst nightmare: that the work he had created to share with an audience would never be seen. Refusing to be screwed over by Weinstein for a second time in his career, Gray was forced to play the long game. He tried to convince himself that, if his film had any lasting merit, it would, eventually, find an audience—even if he had to wait 50, 60 years. Gray had always made films with the idea of lasting artistic achievement in mind; but he had never been forced to reckon with the possibility that one of his films may have to skip over its very own contemporary release. One can imagine what kind of difficult thoughts might emerge from such a waiting period. It was only upon the film’s 2014 release, and its mostly positive critical reception, that Gray was able to get over his depression—it was a gigantic weight off his shoulders. And for a filmmaker who had gone vastly underappreciated in his own country for the first phase of his career, in 2014, Gray said that the tides finally turned: it was the first year that he received more fan mail from America than France. But for a brief time Gray had been forced to reckon with just what it was all about, this filmmaking thing—what was he doing it for? In the landscape of contemporary cinema, Gray looked around and saw that he was alone, absolutely alone—sure, he has director friends that make movies, but none which truly possess “that synthesis of friendship and philosophical alignment.” He understood that, given his specific cinematic personality, he made movies for an audience, rather than the audience. And that with whatever audience he had, he couldn’t just give them what they wanted—he had to give them what they needed. (Something Weinstein couldn’t understand.) Fame is fickle, and not worth pursuing. The pleasure and the purpose had to be in the making of the art and the art itself, to the point where it’s no longer about the individual, but rather what can be contributed to the culture, no matter how small—you do it “for time.” If the film moves just one person, now or ever, that’s great; that’s all you need.

So the only thing you’ve got left, if

that’s the case, that should drive you if you’re an artist—if I may call myself

that—is you try and contribute, as best you can, to this thing that we call

progress. Kind of to push things forward a little bit. And if nobody knows who

you are, that’s gonna be the case. But that’s OK.

__

While Gray was doing his best to stay sane after the premiere of The Immigrant, he did something that he had never done before and has never done again: he worked in television. Not wanting to dwell on The Immigrant’s (non)release, he accepted an offer to direct the pilot episode of The Red Road (2014-2015), a SundanceTV drama. From what it sounds like, he simply wanted to get back to work, to simply work with actors and interpret material to the best of his ability within whatever creative restraints came with the territory. Which were many: no control over its look, its music, its editing, and the list goes on. What Gray considered a terrific script by writer Aaron Guzikowski became very watered down by the time production began. Massively under budget, Gray was under pressure to complete it even though he had terribly inadequate circumstances to do so. He didn’t have control, budgetarily or creatively. Other directors would step in for a shot here or there, and it wasn’t his—without a controlling creative intelligence, as with much prestige TV, everything falls apart. “That show is sort of a symbol to me of the creep of compromise that happens over and over and over. Until it adds up to a mountain of one thousand cuts which leads to the death of it.” Gray doesn’t consider the episode he did his, and admits it’s easily his weakest effort by far—if one even felt like counting it. Gray says that he would maybe consider doing television someday—as many of his director friends have, some successfully, like David Fincher—but that in order to do it he would have to have, for starters, the ability to actually “control what the heck the thing looks and sounds like.”

And as far as this pilot episode, I legitimately cannot recognize

Gray’s touch whatsoever. (Or maybe just one: the presence of Gray regular Antoni

Corone, for less than a minute, in the role of a police captain.) The episode’s

predominating quality is “random episode of TV that a few people watched and

never thought about again.” Without sampling beyond the first episode, I can’t

say how it compares to the rest of the show; but again, it is simply an episode

of television. In a piece about James Gray, there’s really no need to even keep

talking about it, as for all intents and purposes it is not his; when his name

appears in the opening credits, it feels like it could be one of those times

where some random guy just happens to have the same name as a more famous guy. I

think the main takeaway here, with a little extrapolation by me, is how this blip

in Gray’s career represents a part of his great sadness at The Immigrant’s

fate; sunk so low by it, he allows his name to be attached to something entirely

unpersonal just for the sake of getting back to work and fighting off his

depression. Thankfully it didn’t last and he got back to what he’s best at:

making movies.

__

The Lost City of Z, first conceived as a project all the way back in late 2008, would finally begin filming in August of 2015. To say nothing of all the production changes throughout this nearly seven year period, Gray himself had changed, had matured, drastically: 39 at the time of commission, he was now 46—with not only another film under his belt, but another child in his house, among all of the other personal and professional trials that we’ve covered previously. The film is based on David Grann’s non-fiction book The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon (2009), which in turn was based on Grann’s own 2005 article “The Lost City of Z” in the New Yorker. I’ve read the book, and it’s really quite good. Brad Pitt’s company Plan B, who had bought the rights to the book before it was even officially published, sent Gray the book and asked him to adapt it for them. This may have seemed like an unnatural fit—had they seen the kind of movies Gray made?—and yet a similarly surprised and confused Gray accepted the challenge nonetheless. Why not? It was an excuse to expand his horizons: “And I think that I just felt I didn’t want to get stuck. I didn’t want to do just New York over and over again, much as I love it. I needed to break it up.” He wanted to keep making the same film just as any personal filmmaker does—“It’s very different from anything I’ve done—and yet, of course, the same”—but he wanted to make one that was even richer.

Gray started writing the script right away, and finished it in 2010. Brad Pitt, in addition to producing, was signed on to star. It was to be Gray’s next film after Two Lovers. He had spent a number of weeks in the Amazon scouting locations for shooting, as he absolutely wanted to shoot in real locations. But then in November of 2010, everything came to a halt: Pitt withdrew from the role, due to scheduling conflicts. And with him went the money needed to make it. “It's infuriating. The Lost City of Z is a project in which I invested three years of my life, for which I spent a great deal of energy, emotionally and intellectually, and all of a sudden everything stops without me being able to do anything about it. I knew that this could happen, these stories of failed grand dreams are part of the Hollywood myth, but as long as you haven’t lived it, you can’t measure the shockwave.” Gray was no stranger to the whims of stars, on which the financial viability of his films rested—he had waited years for Joaquin Phoenix and Mark Whalberg to become big enough names to make We Own the Night—but it was still frustrating. He has sometimes needed to literally beg them in order to get his movies made. But the Z project had to be put aside; for a time, it appeared unlikely that it was ever going to be made. (At the end of Jordan Mintzer’s 2012 conversation book with Gray, it is implied that the Z project will remain an unfulfilled dream.) It wasn’t until after The Immigrant was made and premiered that the project got back on the burner: in September 2013, Benedict Cumberbatch signed on to replace Pitt in the lead role. But as the late summer start date for shooting approached, Cumberbatch became the second actor to drop out of the role, because his wife was due to be giving birth during the scheduled Amazon shoot. This was February 2015—only six months to go until shooting. Luckily, Gray was able to find an able replacement: Charlie Hunnam, far less known than his two predecessors in the running for the role, but someone Gray loved, especially once he learned that he was indeed authentically English, not American like he had thought based on his famous television role in Sons of Anarchy (2008-2014).

But after nearly seven years, Z was finally being made. Principal photography began on August 19, 2015, in Northern Ireland (Ulster), where for five weeks all of the UK and WWI material was filmed. The war material was torture: Gray, desiring authenticity, had ordered the trenches to be built to their actual size, which were smaller than he had imagined; combined with the mud, it was a nightmare. But for Gray, “the rest of the Northern Ireland shoot was the happiest I’ve ever been making a film. Pure happiness. All you have to do is turn the camera on and the sky does all the work for you.” In September Gray and crew then moved onto the bulk of the shoot in South America, where they would be until October. Gray had originally wanted to shoot in areas as close to Fawcett’s real historical locations as possible; but while scouting, he discovered that much of the area Fawcett had explored had been decimated, the jungle razed for crop farming. They then looked to Peru, in Iquitos (where Herzog had shot 1982’s Fitzcarraldo[1]), but in the decades since Herzog, it had changed drastically. Next they looked at Manaus, a city in northern Brazil, but it was too inaccessible, the infrastructure for filmmaking close to nonexistent. As the process of elimination continued, the next spot proved to be the one: Colombia, in Santa Marta, on and along the Don Diego river.

It was a physically punishing shoot, to say the least. I’m not going to relate a dozen different anecdotes, varying degrees of entertaining and alarming, which one can easily find told more interestingly by Gray and the cast themselves in interviews. Suffice it to say it wasn’t easy, and at times quite dangerous. But Gray was as prepared as he could be. He’d had years to do research and planning, having read many first-hand accounts about his subject: Exploration Fawcett: Journey to the Lost City of Z, a collection of Percy Fawcett’s diaries; Lost Trails, Lost Cities (1953), a collection of Fawcett’s manuscripts, letters, and other records, selected and arranged by his youngest son Brian; Brazilian Adventure (1933), a book by Peter Fleming (brother of Ian, James Bond’s scribe) about his search for the lost Fawcett; and more. The film was budgeted at $30 million (Gray’s most expensive to date, until Ad Astra nearly tripled it).They shot for eight weeks in the mountains, jungles, and rivers of Colombia. The amount of wildlife, as you will often hear in anecdotes from the shoot, was immense.[2] Gray relates that within two weeks of shooting in the jungle, “a kind of madness began to set in.” For the remaining time there, it was a kind of phantasmagoric experience, done in a haze, with the constant ambience of the jungle beating down on them from all sides. The temperatures were of course incredibly high,[3] and as Gray is fond of joking that he has the complexion of an accountant from Minsk, it’s a wonder that he, as well as all of his crew, made it out unharmed. But the experience bonded everyone on set, and in the shared miserableness they themselves became a sort of band of explorers parallel to Fawcett and his teams. Gray’s family even visited for a while, and he has said that his biggest regret on the shoot is that he didn’t have his wife (who’s a documentarian) film a making-of à la Eleanor Coppola’s Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse (1991).[4]

If Gray’s philosophy regarding the direction of his actors had by

this point become a complete removal of the wall between character and actor,

the jungle shoot on The Lost City of Z provided the perfect organic

environment for this to occur. The actors, worn down by their jungle existence,

began to be more and more themselves—their characters took on their own personal

traits. Where Hunnam took on more of a leadership role, always fighting forward,[5] Pattinson retreated into

himself, disappearing into a meditative state. Hunnam, who had been a last

minute replacement in the lead, had the same kind of chip on his shoulder as

Fawcett; an actor who hadn’t been given much in the way of substantial roles,

he set out here to prove himself just as Fawcett had. It was this quality that

Gray saw in him when casting him, as well as his dashing, movie-star qualities

and looks reminiscent of a 1930s Errol Flynn. Pattinson, on the other hand, had

been cast in the movie earlier than any of the other actors. He had

specifically reached out to Gray, as he was to do with many other great

directors: “Immediately after I did Twilight, James was the first person I

wanted to work with—I sought him out—because you get in a James Gray movie and

you get a good performance.” Gray didn’t know any of the Twilight movies,

but he had seen him in David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis (2012), finding him

weird but arresting—he was able to slot him into the role of Fawcett’s

aide-de-camp, Henry Costin. While in the jungle, both Hunnam and Pattinson sunk

into their roles so thoroughly (or rather, their roles sunk into them) that

Gray often stole shots of them when they weren’t aware the camera was

rolling—you can tell while watching the film which moments these are, for

example the shots of them lounging around emaciated and seemingly half-dead on

the river raft during their first journey. They didn’t have to act, really. In

the sublime scene also during that first journey, where Fawcett has Costin paraphrase

his wife’s letter to him to ease the difficulty of hearing it, the slow zoom-in

on Hunnam’s face next to the fire feels like a moment of pure capturing, the

physicality and emotionality of his face undifferentiable between actor and

character. Besides Sienna Miller as Fawcett’s wife and a host of great

character actors in bit parts (Angus Macfadyen, Ian McDiarmid, Clive Francis,

Harry Melling, and Franco Nero[6]), we have Tom Holland, the

little boy who apparently has yet to be graced with a role as good ever

since he donned the Spidey suit. The part fits him to a tee, despite or even

because of his boyish movie star charm, as his character Jack Fawcett was

historically very interested in movies, and even planned on becoming an actor

after returning from the trip that he ended up never returning from.[7]

__

Italian directors start out like

Rossellini and end up as Visconti. Even Rossellini and Visconti did.

– D.K. Holm, Film Soleil (2005)

If we can slot Gray in with the Italians, and he would surely be gratified if we did (they’re his favorites), then we can maybe see how this statement applies to him. Beginning in a kind of urban neo-realist mode with his first couple genre films, by the 2010s he had found his way into a style less realist and more decadent, more stylized, more... unreal. After his period film The Immigrant, which was simultaneously post-genre and a kind of new genre altogether, The Lost City of Z finds Gray staying in the past but returning to genre, albeit in a roundabout way. Z fits nicely enough in the “adventure movie” category, a genre that—compared to the crime thriller mode his first three films worked in and around—is more or less dead. It’s a throwback genre, to the “exotic” films of classical Hollywood or the big-budget epics of the cinemascope, let’s-get-folks-back-in-seats post-TV era of the ‘50s and ‘60s. It’s a historical epic in its own way—Gray’s longest film (with a first cut of over four hours), and also his only film to be set over a period of multiple years—and while hardly financed as an expected seat-filler, it has the feel of a Studio Film crossed with a European artistic sensibility.[8] Although for what it is, it appears as Gray’s most concerted effort up to this point to reach a popular audience, catering to them with a certain amount of spectacle while remaining personal. Criticized by some for changing the historical Fawcett’s story—he was more racist in real life, he went on seven trips to the Amazon not three, he became a kind of Eastern religious crackpot, etc.—Gray was in fact doing this for the purpose of inducing the most openness in an audience as he could, removing anything that could hinder emotional vulnerability to the man or the story in order to get rid of as much distance as possible between film and viewer. With these two historical films, we could maybe say that they’re Gray’s only films which touch more or less directly on so-called “relevant” topics—immigration in The Immigrant, nationalism/colonialism in The Lost City of Z. (By all accounts, Gray’s newest film Armageddon Time outdoes both in stabs at “relevancy,” for what that’s worth.)

But even if there is more of an opening up to a popular audience here, the film is certainly no less personal for Gray. It’s personal, but in somewhat of a new way:

By the same token, Gray acknowledges that the old screenwriter’s adage “Write what you know” has its limits. “The great pictures of the filmmakers we admire, from the studio system in particular, but even the European filmmakers of the ’50s and ’60s — they weren’t home movies,” he says. “They made films which were expressing their personal sentiments using other genres. And in a perverse way, I may be too close, have been too close, to my subjects.”

It's a line that Gray has explicitly said, about something like Two

Lovers: that in a way it was just a cheap home movie. The Lost City of Z,

being the farthest from home Gray had ever gone, was also the farthest

thing from a home movie he had ever done. But even while he was toiling within

a genre metaphysic that is traditionally escapist, Gray locates his interest in

it in a different way: “Adventure films only interest me if they are deeply

intimate. The adventure here is interior, the jungle could be replaced by

anything. What matters is the quest, a romantic, relentless, and, of course,

secretly tragic quest.”

Ironically, it’s in such genre material—material which is Gray’s first and only adaptation of someone else’s work, and, having been commissioned to write and film it by an outside source, technically his most mercenary work, in a small but essential sense—it’s in such material that we paradoxically find Gray’s most personal work to date.

It's maybe the most Grayian a Gray film has been, whatever that means, even if it seems to mean something that doesn’t quite seem to be true. Contrary to his past practices, for The Lost City of Z Gray didn’t watch any movies. “Because we didn’t want to replicate other movies—we wanted this to have its own rhythm.” Or maybe just one: Gray says he showed Khondji The Leopard (1963) for its attention to detail re: “the depth and breadth of the production design and set decoration,” what he calls “layers.” And layers not just of aesthetic depth but also of thematic depth, clearly, since the two combine as the main starting point aesthetically: “For The Lost City of Z we watched nothing. Instead, we started by looking at the jungle as a projection of protagonist Percy Fawcett’s desire, not as necessarily a tangible adventure movie.” In this sense it is very Viscontian, and late Viscontian at that, where desire is often the driving force, although it’s more tragically impotent there than it is here, where Fawcett does actually reach some kind of peace. And you also have that Viscontian zoom at the Viscontian ball at the beginning of the film, part of a formal system here that is incredibly fluid and gentle. Pattinson remarks that “as an actor, you feel as if he’s very in touch with the movement of the cameras—there’s a kind of rolling aspect to it.” It’s new formal territory for Gray, further even than The Immigrant, it’s closest relative, which had already been much further than anything previously. “In Lost City,” said Brad Pitt, “this guy has really evolved into his own thing. He knows everything he could about his masters, but he’s made it his own now. I perceived it as being really open.” Gray himself says something similar: “I had wanted, not to turn my back on my previous films, but to detach myself from a certain practice of cinema.”

Making a film outside of America for the first time, given his characters Gray was essentially making a British film—kind of like the Bronx-born Stanley Kubrick, who one can mention in passing with two interesting tidbits: one, Khondji says that the film’s war scenes were inspired by Georg Krause’s camerawork in Paths of Glory (1957), and two, Barry Lyndon (1975) actor Murray Melvin (Rev. Runt) makes a cameo appearance at the age of 83 presiding over the opening banquet. Another British cinema reference comes courtesy of Kent Jones, who informs us that Gray was inspired by The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) from a structural standpoint. But the real big British name that comes up in writing on the film is David Lean,[9] although the only thing Gray himself mentions about him is that the idea of Z was “to present a David Lean movie with a bit more 2016 politics.” It’s a fair point of comparison, even if the burden lies on us to extrapolate on it. I almost think it would be more fruitful to talk about Lean’s Summertime (1955) in relation to Two Lovers than any particular film in relation to Z. Maybe the late jungle scenes of The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), which are infused with a similar mystical, mythical, magic light and shadow amidst nature. Or perhaps Lawrence of Arabia (1962), where there is the same romanticization of the desert by Lawrence[10] as there is by Fawcett of the jungle, the same metaphysical relationship between one man and one exotic environment. Famous for its cut from blown-out match to desert, The Lost City of Z retains some of this classical movie magic, some of its classical adventure momentum via propulsive editing, especially in two particular moments that are explicit, playful uses of the match cut: from a river of liquor running down a sink to a train running across the countryside, and later a rising camera movement that starts on an Amazonian spear in Fawcett’s home and cuts to a rifle bayonet in the dirt at the Battle of Somme.

Gray set out to avoid the tea & crumpet-ness of British cinema, however, a goal which he saw as achievable by grafting an “Italian expressiveness onto the English countryside.” The UK-set scenes in the film pop off the screen like classical paintings, which makes sense as Gray and Khondji have said they were more inspired by paintings than films—especially, for the UK, by a decent-sized list of landscape painters: Claude Lorrain (1600-1682), particularly for his skies; Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875); Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721); J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851); also the paintings of social realist painter Eyre Crowe (1824-1910); and Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788).

|

| Landscape showing the flight into Egypt (Claude Lorrain, 1647) |

|

| Les berger sous les arbres (soleil couchant) (Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, 1853) |

|

| The Embarkation for Cythera (Jean-Antoine Watteau, 1717) |

|

| The Temple of Jupiter Panellenius (J.M.W. Turner, 1816) |

|

| The Bench by the Sea (Eyre Crowe, 1872) |

|

| Landscape in Suffolk (Thomas Gainsborough, c. 1750) |

Meanwhile for the Amazon scenes, Gray and Khondji were enamored with the jungle scenes of Henri Rousseau, although the inspiration is more spiritual than literal—more for the idea of the jungle than the jungle itself: “the jungle as a dream.” Gray saw Rousseau as having a similar approach to the jungle as himself; there was something childish about it, ”filled with hidden things,” with a melancholy beauty. Just like Rousseau, painting in the so-called “Naïve” or “Primitive” manner, Gray was taking a Western approach to “what the jungle is, means, and looks like, yet there is a humanity to it and a love of it. Ultimately there’s a mystery to it.” One of Gray’s friends, a sculptor/visual artist named Thomas Houseago, was shown the film and he said, “James, the movie is a masterpiece, and it looks like a painter made it. You’re a painter.”

|

| The Dream, 1910 |

He’s not wrong. Painting was Gray’s first love and when he traded in his paint brush for a film camera the impulse never left him—new tools for a similar purpose. And the older Gray gets his films seem to be getting more and more painterly, cinema melting away for something more im-/expressionist. More and more, Gray films only look like themselves. For Z, Gray and Khondji “wanted to be less reliant on outside references.” Much of the aesthetic inspiration came from actual photographs from Fawcett’s expeditions, some reproductions of which we see in a photo montage late in the film. Additionally, the autochromes that Gray used for reference on The Immigrant were another major visual inspiration here, especially the UK material, with their desaturated, technically “wrong” color that is still very painterly. Both of these old-time photographic inspirations parallel with Gray’s decision to shoot, once again, on 35mm film.

It was always in my mind to stick with 35 for this kind of story. May I state, also, there are some filmmakers who work just beautifully, digitally. I mean that’s a different medium, it’s like saying “painting water colors” or “painting oils,” you know, it’s not the same medium. And I had felt that one of the great things about 35 millimeter film, which makes the image up in grains, obviously, is something you might call temporal resolution, because these grains change their position, every frame to frame. Whereas the digital images, pixels, they stay fixed as a grid from frame to frame, so the film has a different feel.

Film and digital are two different mediums, and Gray has (until his most recent film) always worked in the former. It’s his preferred medium, and that’s his artistic choice to make (and he should be able to make it—I have absolutely nothing against digital, but if it gets to the point where shooting on film isn’t even an option, something went wrong....) Each has its own connotation—aesthetically, emotionally, and philosophically. For The Lost City of Z, it made sense to use film, conceptually. Gray mentions Susan Sontag’s book of essays On Photography (1977), and a suggestion she makes about the irretrievability of film, the inherent melancholy and pathos of the film image: “All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” For a film that melts away along with the passage of time, descending into a dream as it nears its end, there’s something very fitting about its primary existence as a piece of material film that will itself degrade as time goes on. Khondji also used vintage lenses from the 1950s and ‘60s, and he deliberately under- or over-exposed the film in places during the jungle scenes in order to “make it feel like they’re in the shit,” causing the film grain to really blow up and lose detail.[11] Ironically, the option to shoot on film turned out to be a wise decision practically as well. With high humidity levels in the jungle, much of the digital technology the crew took along quickly ceased to function. The analog technology of a film camera, however, withstood the elements. But shooting on film was still risky in another way, as it was a crapshoot on a daily basis as to whether the footage actually made it to the lab to be developed (all the way in London). They trained a local man in the art of film loading, and every day he would take a day’s worth of footage and put it in a cardboard box, which was then put on a single-engine prop plane, which took off from a makeshift runway, and flew away with the day’s work, first to the local airport in Bogota, then to Miami, and finally to London. It wasn’t until around noon each day that they learned, via satellite phone, whether or not the film had even made it to the lab.

This plays into a meta-commentary that parallels the film itself, a

part of the madness which descended upon Gray and crew a few weeks into their

jungle shoot[12] and

something that weaves its way into the film via some very subtle sound work.

Sound designer Robert Hein (a collaborator of Gray’s on this as well as the two

films bookending it) created low, sub-frequency drones which appear throughout

the film that are designed to go unnoticed and work on a subconscious level.

These drones were created out of natural jungle sounds, sonically manipulated

into unrecognizable shapes and subtly deployed on the film’s sublevels. The

whole film is sonically dense, and also in a way that forwards the film’s theme

of crisscrossing civilizations—sounds from the jungle will appear dotted around

UK-set scenes and vice versa, merging the Amazon with Victorian England,

playing with the complexities of Fawcett’s half-in-one-place-half-in-another

spiritual psyche. It’s done visually at the same time: as we keep going back,

vines and vegetation seem to be slowly overtaking the Fawcett family home. The

film always seems to be mingling with something in the air, the haze of the

jungle seeping into every frame (whether literally there or not); watching it,

I almost feel a kind of floating sensation.... This sensation is probably

helped by the music, which mingles a beautiful Spelman score with classical

selections: Bach, Beethoven, Verdi, Gabriel Fauré, Mozart, Johann Strauss II,

Mahler, Stravinsky. And, above all, Maurice Ravel, whose mind-meltingly

beautiful Daphnis et Chloé (part 3: “Lever du jour”) acts as the film’s

main musical motif, so in tune with the images that one wonders if Gray adapted

the film from that piece rather than David Grann’s book. From its first use to

its final appearance, the piece takes on a new connotation, whisking Fawcett

and his son away towards their destiny. The movie’s play with time here is

marvelous; we see it represented simultaneously sonically and visually when

they return to the spot of Fazenda Jacobea, what on Fawcett’s first journey was

a small village tucked into the jungle, greeted by a production of Mozart’s Così

fan tutte. On the final return journey, the village has been swallowed up

by the jungle, the little opera stage with it—on the soundtrack, merely the

whisper of that Mozart opera, once again the Act I scene III “Eccovi il

medico.”

__

Despite being the film farthest from Gray’s home turf—and the

conflicts which have animated it since his childhood—The Lost City of Z is

maybe his most direct confrontation of not just the idea of class, but of its

human weight, its burden, and its role as a kind of catalyst—class as whip,

simultaneously self-flagellating and self-motivating. In reading David Grann’s

source material that he was set to adapt, Gray zeroed in on what in the book

are just a few lines, a mere hint: passages about Fawcett’s father losing the

family fortune (twice over) and the effect that had on the son. The father had

started as the equerry to Prince Edward, but had drank and gambled his money

away. Grann locates in Fawcett’s pre-geographical activities the desire to flee

the kind of class environment his father had fell from: for example, “[Treasure

hunting in his spare time in Ceylon] was also a chance to escape from base and

its white ruling caste, which mirrored upper-class English society—a society

that, beneath its veneer of social respectability, had always contained for

Fawcett a somewhat Dickensian horror.” Fawcett’s dilemma in the film is that

his distaste for the respectability of the upper classes must dual with his

desire, nonetheless, to be recognized for his achievements—by this very same

class. Gray took a feather out of Visconti’s cap here in a certain approach to

the material having to do with “Visconti’s political bent, which was an

interesting Marxist read of history. It’s interesting because it’s not just

Marxist—it’s aristocratic Marxism, because he was a count. That appealed to

me.”

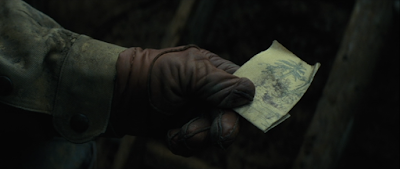

What Z ends up doing is tracing one man’s journey from attempting to regain the class rank his father lost to transcending class altogether via harmony with something higher, something non-material. But it’s a leap made via an obsession, a deadly, all-consuming obsession. Obsession as class escape—this is Fawcett’s route away from a concern with status and towards a concern with deeper, more human truths—the cultural enlightenment that he berates the Royal Geographical Society members with during his thunderous speech upon his first return. The central thread for Gray re: Fawcett’s obsession, the single most significant idea he took from Grann’s book, was that “here was a person for whom the search meant everything.” On page 29 of his book Grann describes such obsessives as people “who get some germ of an idea in their heads that metastasizes until it consumes them.” Z, Fawcett’s lost city, takes on more meaning for him than any material discovery could actually give him. The search becomes the destination, in a way that is half-beautiful and half-tragic. He can’t stop thinking about it, even in the midst of war. Fawcett holds onto a small paper drawing of the jungle, which acts almost as a kind of prayer device before he storms into no man’s land and faces hell on earth; ending in his near-death and temporary blindness, the camera dollies to this drawing caught on a piece of barbed wire (an homage to the dolly to the blood dripping off the boxing ropes in Raging Bull). Before this, in the trenches with his men, Fawcett speaks with a fortune teller (Elena Solovey, a friendly face from many other Gray films) in a scene dripping with emotion and yearning: as Hunnam tearfully relates his deepest desire of finding Z, the camera slowly circles around the little dirt cave—panning past the profoundly moving faces of the men, mostly young and about to die, in a moment straight out of a Terence Davies film[13]—and then cutting its way back to Fawcett where the background has been transformed into jungle scenery; the desire made manifest, visually, in this most rotten of situations. The visual trick comes cribbed from Richard Fleischer’s The Boston Strangler (1969),[14] another movie which starts in a classical manner only to melt down at the end.

But the theme of using an obsession as a way to escape a hostile and/or rigid culture wasn’t just Fawcett’s thing; it’s Gray’s. He understood it, he empathized with it, because it’s him too: the filmmaker who was told he couldn’t become a filmmaker, who strives to transcend the very idea of class by searching after things that nobody else understands—the artist’s search for beauty, above and beyond any commercial considerations. Class considerations are in Gray’s blood: his mother was incredibly class conscious, “literally haunted by the idea that you had to rise up socially at all costs.” And the first twenty years of Gray’s career as a filmmaker were, like Fawcett, similarly haunted by a certain failure to gain recognition for his achievements, especially in his home country.

“It becomes very personal to you.”

Percy Fawcett is James Gray. The searcher after beauty who leaves

his family for the jungle, the person who spends years on his obsessions away

from his family and who usually meets with “failure.” Gray and Fawcett even

have the same family arrangement of children: two boys and a girl. Gray wasn’t

just making a film about Fawcett; he knew him, on an intimate level,

emotionally:

... so I thought, OK, I can understand that. I can understand a person who feels disrespected, who wants to prove himself, who feels shut out... That moved me, that was very emotional to me. And all the period stuff, all the trappings of that and then going to the jungle honestly came second. It always starts for me with character, and I felt sympathetic to him.

As we’ve seen with previous Gray films, each seems to have a secret heart, a spot in which James Gray the human being reveals himself to the core: I think, for The Lost City of Z, this is that spot. Gray’s desire to not be looked down on or condescended to. A craving for acceptance. In a way, Gray says, Z is really just about a loser from Queens who wants to prove himself, someone who wants to do “something that means something to the world.”

I feel every time you make a film, in essence the character becomes a stand-in for you. That moment is an example of how you’re always trying to personalize the material by coming up with an equivalent in your own life that would give you the same feeling.

When Gray embarked on making this film, he was a decade younger than Fawcett when he went on his final journey. And even in a matter of weeks, despite the intense physical trials, Gray came to understand the appeal of the jungle. “It’s the most heightened form of your existence.... The jungle is exploding with life. You cannot fall asleep at night, that’s how loud the insects and animal life is. Would I ever go back? If the material was right, I would. Yeah, I would.” The jungle seeped into Gray. He grasped it’s metaphysics, in a way. It’s like what Pattinson says in the film: “The jungle is hell, but one kind of likes it.”

Similar to The Immigrant, The Lost City of Z doubles as a kind of private therapy for Gray. In the end, Fawcett becomes a kind of projection, an avatar through whom Gray accepts things that Gray himself has a hard time accepting.

I saw Fawcett’s struggle, his need to feel inside the club yet knowing he is outside of it, and his gradual progression to a place where being outside of the club didn’t matter to him. I felt that was a beautiful movement of character. I’ve not gotten to the same place that Percy has yet.

If, as Gray says, the job of the film director “is to reveal that part of ourselves we are least comfortable with,” this striving to be accepted is just that. Something that Gray is a little ashamed of, ashamed of the fact that he hasn’t been able to live up to the ideal of a personal art totally unconcerned with how certain groups of people receive it. But having traced the arc of Gray’s own career up to this point, and knowing how it continues, something tells me that one day, sooner or later, the arc of Percy Fawcett traced over multiple decades in this film will also be Gray’s. We can already detect it here, simply by the fact that Gray put it in a film—even if it’s just a goal to be reached, the fact that Gray can name it and embrace it through a fiction means that he’s far closer to embracing it in real life than he was at the beginning of his career. After winning a prize at Venice for Little Odessa (1994), part of Gray expected—and probably considered himself deserving—of being recognized throughout his career with more prestigious awards. He’s not won an award at a festival since. It wasn’t until Two Lovers that Gray stopped reading reviews of his work—marking a shift in his maturity which that film, and the ones after it, bear out.

The Lost City of Z brings about another shift, this time as much a matter of content as concept. It’s the first film in Gray’s career that brings about a kind of perspective shift: from sons, to fathers. Gray, 46 at the time of the film’s making, is no longer the son that we see variations on in his first four movies; he has three kids now, and the role of father has become not something to reckon with from a distance, but from right up close, inside himself. And not just as a father, but as a husband as well. “I believe that my feelings were very close to what was playing out between this father and this son, the evolution of this relationship,” Gray says. Which was partly a representation of Gray’s relationship with his own father and how that relationship had evolved; so Gray personalizes both the father and the son role here, making it a two generational story both for the characters and for himself. (A similar dynamic will play out in his next film, Ad Astra: it’s a film as much about Gray’s father as it is about Gray as a father.) Through the repeated absences of Fawcett the father, here, his son comes to despise him; the most moving arc of the film is their eventual reconciliation—for Gray, “this is the real great love story of the film.” It reminds me of something all the way back in Gray’s first film, Little Odessa: Maximilian Schell’s monologue in bed about how through the passage of time the son starts out adoring the father, then hates him, then eventually comes back around again to believing he was right the whole time. But the film is dotted with these little moments of tremendous force which detail the complexities of their relationship. Even in the Amazon his son comes to mind; facing a volley of arrows, one punctures the bible he is holding up in a gesture of peace; just inches away from his face, all of a sudden we are given a flashback to his son’s baptism.[15] Coming home, greeted with an understandably upset child given his absence, a screaming match ends with a slap which sucks the air out the room, an emotional gut punch. “One day you’ll understand your father,” Nina says. The emotion just ratchets up from there: in the hospital with war wounds, blind, Fawcett reconciles with his son in unbearably moving fashion. Eventually, the son becomes the father: he wants to go on his final journey with him, foreshadowed in the beginning hunt when Fawcett says they’ll go hunting together one day.[16] They go, saying and then waving goodbye to the mother and siblings left behind—the scene that Gray said he felt the most emotionally connected to in all the film. Leaving on the train, Gray cuts to images of the children’s beds flashing by (a technique stolen from the end of Fellini’s I vitelloni [1953]). By the time they’re captured by indigenous natives in the jungle, tied and sitting next to each other on the dirt, facing what appears to be almost certain death, the film reaches total, utter simplicity:

“I love you father.”

“I love you son.”

It’s maybe the most moving exchange in all of Gray’s films. Especially coming after failed and/or lesser versions in previous films. When Edward Furlong mumbles “I love you” to his brother Tim Roth, he’s met with silence. When Whalberg tells Phoenix “I love you very much” at the end of We Own the Night, it’s reciprocated (“I love you too”) but Phoenix is a hollowed-out version of himself, more tragedy than hope. But in Z it’s full-on, earnest, from-the-gut, real love, between father and son, facing down their destinies together—it’s unabashedly sincere.

The last twenty minutes or so, leading up to this point and then beyond it, move into the territory of the abstract, dreamlike, the film disintegrating into pure poetic reverie, flying on the wings of Ravel as it reaches upwards, upwards, upwards like Fawcett’s hand reaching heavenward as he is carried along by the natives down a torch-lit passageway to who knows where....

It’s the longest extended grace note in Gray’s cinema, these last few reels, and its difference from the rest of the film is intentional. “I intended to set that up as a classical movie but one that would fall apart at the end. The first bit would feel very classical, and then disassemble.” It’s all in the structure, the narrative. Around this time, Gray shared that his tastes had undergone a shift: no longer were his favorites the mid-century European classics he grew up on, or the New Hollywood that came in their wake, but rather he was obsessed with classical Hollywood films of the 1930s. Following that idea, and his stated love of Busby Berkeley musicals, I had the thought that The Lost City of Z could very well be said to take its structure from a 1930s Hollywood musical: the first part of the film would be normal, almost banal, but as the ending approached it would burst out into a completely different, poetic mode, nearing the abstract, pure lyricism. But this only works, at least in this specific way, by the use of narrative; you need a narrative in order to have a narrative that falls apart. This is a crazy thing for me to say, but Gray’s films are almost.... boring. Until the end creeps up, that is, and everything that has gone before it snaps into place. The narrative is an edifice, and the glorious heights it builds to are reliant on an almost banal foundation. One could even say that the first 100 minutes or so of The Lost City of Z are banal, that on their own they mean close to nothing, that without the final twenty minutes or so there is almost no use in watching the film. But this is narrative: where each element sits in its place and contentedly accumulate to form an overall film. A film—not just a collection of scenes and moments, but a film. One whole, autonomous work of art that says something to us, that communicates something to us, that we think back to in our minds after viewing and see as one grand gesture towards something greater than any of its constituent parts. The idea, says Gray, was to make the first part of the film interesting, to keep the audience engaged, and then for the ending to land like a ton of bricks. (An emulation, says Gray, of the storytelling style of Fellini’s Amarcord [1973]). This may sound blasphemous coming from someone who has spent thousands of words analyzing Gray’s form by this point, but I don’t really even consider Gray some kind of all-time great formalist. He’s no Welles; he’s no Kubrick. He’s a good formalist, who just so happens to pack enough punch in the realm of emotion to not only overcome that fact, but to transform it. In the realm of form, all he ever has to be is “good enough”; the narrative, the emotions, do the rest. And they do it so well that there’s no need to even judge the form in a conventional way, and even if one were to do that, the form appears better for the simple fact, metaphorically or literally, that we can’t see it through our tears.

It’s the longest extended grace note in Gray’s cinema, these last few reals, and it’s difference from the rest of Gray’s films is essential. What we have here is nothing less than the first moment of true acceptance of fate in a James Gray film. “Nothing will happen to us that is not in our destiny,” Fawcett tells his son. This before he gives himself up to the natives, to do with him as they will. This is not a dramatic encounter of conflict. It’s a mere occurrence, one that Fawcett accepts without hate or anger or regret or pain. (From the meeting with the native tribe that helps them on their way, seen in the beautiful photo montage, to their capture by a different native tribe, one gets the feeling that hundreds, thousands of years of indigenous history and the West’s relation to them is being pondered on a deep level within the film—that Fawcett’s final journey to “the beyond” is not only an acceptance of his fate, but a transcendental meeting place between two macro-cultures/ways of life. There is no hate for these people, but an awe-full encounter on the level of the purely human that is tinted with hundreds of years of pain and misunderstanding.) The letter that Nina reads Fawcett on the occasion that he doesn’t return (in a fantastical, ostensibly un-Grayian time jump scene) relates that "to search for beauty is its own reward," and concludes with a tidbit from the Robert Browning poem "Andrea del Sarto" (1855): “...but a man’s reach must exceed his grasp, / Or what’s a heaven for?” Fawcett achieves this transcendence of the search. He doesn’t reach his goal of finding Z but he finds something more essential, something non-material. He has transcended class and his own class strivings, achieving a “success” that to the casual observer looks like failure. The struggle to rise up is no longer there, traditional success has become meaningless, and in their place is the pure and simple search for beauty, for sublimity. By the end of Fawcett’s final journey, it has become Gray’s most peaceful film. “I asked myself a basic question,” says Gray. “Is the story a tragedy? The answer to that question I think turned out to be no.” Fate—that thing which has haunted Gray and his films through his whole career—is here no longer tragedy, but transcendence. Fate is no longer dreaded, but embraced. It’s hard to overstate how much of a significant maturation this is for Gray; the final moments of Fawcett giving himself up, headed down to the river, the camera drifting up to the ascending smoke—this may be the most significant sequence in Gray’s career, not just on its own but as an answer to the films that came before it. It’s a step forward. And, in the context of the near unbearable force of Gray’s early movies, incredibly moving.

But the film doesn’t forget, amidst all this transcendence, that

there is still a tragedy here; and we shouldn’t forget it either. Sienna

Miller’s Nina is left behind, losing a husband and a son and with little sign

of hope that they will ever return—a fate worse than knowing for certain of

their death.[17] She’s

the Penelope to Fawcett’s Odysseus: “one of the few who believe,” as Nina

herself once said. Miller plays the wife-at-home role with a vigor that overcomes

the stereotype (as she did just prior in Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper,

too), and Gray films it that way. That the movie ends with her is significant; and

it subverts the common criticism of Gray that the women in his films are less

than full creations. In a sense, Gray’s films are really very much about women,

examinations of the way men relate to them and their failures in how they do or

do not do that. Most of the women in Gray’s male-centric films are classically

tragic figures: Moira Kelly in Little Odessa, Charlize Theron in The

Yards, Eva Mendes in We Own the Night, Sienna Miller here. In

reverse proportion to their screen time, relatively less than their male

counterparts, they make twice the impression. But Miller is the first real wife

figure in a Gray film, and their marital dynamic brings out an essential

dialectic that the film follows through on from their first conversations to

their final separation. Their argument before Fawcett’s second journey—Nina

wants to go with him, he won’t let her—is essentially unsolvable. Both make

good points, even if they appear a bit cliché (in patriarchal and feminist ways,

respectively); it’s true that Nina’s burden is disproportionate in dealing with

his absence and raising the children, but it’s also true that she would be a

burden on their exploration if she went along. But it’s not about who is

right—it’s about the validity of each of their respective desires and emotions.

To make it more personal to Gray, he tells us that this scene was based on a

conversation he had had with his own wife; and, after shooting finished, Sienna

Miller revealed to Gray that she had based her character on his wife. Just like

Gray’s previous few films, the ending of Z has two irresolvable

elements, here split into the two characters. Fawcett gets transcendence, Nina

gets tragedy. Fawcett has embraced fate, whereas Nina is forced to “take the

rough stuff that Fate has ladled out to [her] for such a long time,” as her

remaining son Brian would write about her. In this dialectic, I’m reminded of

Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), where Richard

Dreyfus’s father character abandons his family for transcendence—he achieves

it, but at the tragic expense of the family that gets left behind. (Another

film, now that I think about it, that begins classically and then falls apart

into extended poetic reverie.) As the haunting final image of Z suggests,

the jungle didn’t just swallow Percy, but—in memory, in mind—Nina as well.

__

The Lost City of Z premiered as the closing night film of the 2016 New York Film Festival, and was released in U.S. theatres in April of 2017 by Amazon Studios and Bleecker Street. Given that I had first discovered Gray’s films in 2016, this was my first chance to experience a new Gray film in theatres. I went twice the first weekend, and I’ll never forget the daze that I left the theatre in after both viewings. A direct line can be traced from that weekend to the fact that you are reading this right now.

... you can forget all of the rest of the stuff about history and politics and what you’re trying to say with a character; and in the end what you’re really trying to do is to convey a non-verbal feeling that you have always felt from within.

And so when you talk about the first three and the last three what you’re really talking about is this divide, that now looking back I’m very conscious of and it started with Two Lovers where I became very convinced that I was gonna put myself in that movie. I am, in part, Leonard Kradditor. Now, it’s not my story autobiographically, I wound up marrying this incredible woman.... That’s not my personal story at all. But the struggle that Leonard has, the struggles over the idea of his desire, that’s personal; and I wanted to decouple it from the autobiographical. And The Immigrant was the same way, that that woman, the questioning that that woman had, where she had to reject—where Eva had to reject her Catholicism and everything she was taught from the crib to believe, in order to attempt to save a loved one, but how conflicted she would be, how tortured she would be—that is personal to me. And Joaquin is personal to me in that film. And Percy Fawcett in this film, Charlie is personal to me. That the world, the world is a beautiful and terrible place, and the more that we can embrace that in the work, the more we make it about—not about us in some solipsistic or narcissistic way, but the more that we can make the work an expression of our state of soul, and make ourselves be vulnerable, so that when people say “you’re movie is shit” it hurts us, and it’s good that it hurts us; because if it hurts us, it means we put a lot of ourselves into it. You know the people it doesn’t hurt when somebody says “I hate that guy’s movies” or “that woman’s movies”? It does not hurt the people for whom it’s a business.

All of my efforts when I make a film are a removal of the wall of irony and cynicism. It’s a huge wall, a high wall. So each film is an attempt to break down that wall just a little more, and to express ourselves clearer and more straightforwardly and more sincerely. The closer we get to that, I think the greater the film

You know, the best advice I ever got in my life...

was the great Francis Coppola, and he said: “Just make it personal, James.

There’s only one of you.” Which I thought was so great. So the closer you can

come to revealing yourself, I think the better the work is. In candor with you,

I think that the first couple of pictures that I made—I tried, I wasn’t not

trying, but you don’t know who you are yet, really. It takes a few years before

you can really understand what it means to reveal yourself. I’m getting closer,

I’m not there yet maybe, but I’m trying.

[1] The Lost City of Z’s relation to Herzog’s two famous jungle movies isn’t as significant as the many mentions in the press make it out to be (its mostly a matter of surface similarities), but Gray tells us that his wife did read Herzog’s Conquest of the Useless: Reflections from the Making of Fitzcarraldo (2009) before filming began. “You should read it. We’re going to go off and do this,” she said. Gray replied, “That’s the thing I don’t want to read.” Although this passage from Herzog’s book accidentally offers great insight into how The Lost City of Z is a James Gray film:

The Grand Emotions in opera, often dismissed as over the top, strike me on the contrary as the most concentrated, pure archetypes of emotion, whose essence is incapable of being condensed any further. They are axioms of emotions. That is what opera and the jungle have in common.

[2] Speaking of wildlife, Gray said that while

they got most of the footage they came for, the one thing in the script that he

wasn’t able to figure out a good way to shoot was a scene of Fawcett

encountering a giant anaconda snake: the CGI one didn’t look convincing, and

the mechanical one didn’t work. But another animal shot they did get is worth

sharing: the black panther which Fawcett kills, saving the band of explorers

from sure starvation, was played by a real panther that once belonged to Pablo

Escobar. It was just a cub when he died, and they were able to import it from

his zoo in order to get the shot.

[3] Extreme weather seems to be a kind of theme

in Gray’s filmmaking career: Little Odessa had been shot in the dead of

winter (dozens of blizzards, and the coldest recorded in NYC history up to that

point) and The Yards had been shot in the dead of summer.

[4] It’s worth dispelling the rumor (printed in

many places as fact) that Francis Ford Coppola, upon learning that Gray was

going to shoot a movie in the jungle, told him “don’t go.” It’s not true, and

only made its way to print because Gray had joked about it when talking about

the real story of where the “don’t go” line came from, which was actually

something Roger Corman had said to Coppola after he asked for advice about

shooting in the Philippines.

[5] I don’t know how this happened, but it’s

become a joke between me and my sister where I will once in a while randomly

proclaim, in my best Charlie Hunnam impression, “There’s no going BACK! It’s

RIGHT HERE.”

[6] Famous for playing the title role in the spaghetti western Django (1966), Nero is another actor, along with Tomas

Milian and Tony Musante, who has a bit role in a Gray film after starting in

Italian genre cinema. He also married, in 2006, another James Gray performer:

Vanessa Redgrave.

[7] Some relevant passages from Grann’s book:

With his stylish clothes, he [Jack] looked more like a movie star, which is what he hoped to become upon his triumphant return. (14)

In New York, the young men had relished the constant fanfare: .... and the motion-picture palaces, which Jack had haunted day and night. (16)

While Fawcett had

been away [on his 1921 expedition], Nina had moved the family from Jamaica to

Los Angeles, where the Rimells had also gone and where Jack and Raleigh had

been swept up in the romance of Hollywood, greasing their hair, growing Clark

Gable mustaches, and hanging around Hollywood sets, in the hopes of landing

roles. (Jack had met Mary Pickford and loaned her his cricket bat to use in the

production of Little Lord Fauntleroy.) (183)

[8] To recall an earlier comparison with the

filmmaker Bob Rafelson, who sadly passed away at the age of 89 this year: if Little

Odessa (1994) is Gray’s The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), then The

Lost City of Z (2016) is his Mountains of the Moon (1990).

[9] If David Lean is not a direct connection, he is very much an indirect one, as Gray’s beloved Visconti was an admirer of his. A favorite story of mine, from Gaia Servadio’s biography of Visconti:

[Visconti] loved to go to the movies. “We would go to the cinema almost every night, at 10.30,” said Peppino Patroni Griffi, the playwright. Once, when they both went to see Doctor Zhivago, which Visconti liked very much, as they were leaving the cinema, Visconti whispered to Griffi: “Let’s go upstairs and see it all over again, hiding, otherwise they’ll lynch me.” He knew he was not “supposed” to like the film intellectually.

[10] Another connection: the historical T.E.

Lawrence once volunteered to go with Fawcett on one of his expeditions, but

Fawcett declined as he was wary of him and his fame.

[11] Not ever having the chance to see the film

projected on film, I defer to someone who has. On the Film Comment podcast,

Michael Koresky once said, referring to Gray’s modeling of the jungle scenes on

Rousseau: “I got it intellectually when I saw it on DCP, and I got it

emotionally when I saw it on film.”

[12] Many people went straight for the Apocalypse

Now comparisons as soon as the film premiered, which is understandable on a

certain level (look, Gray loves it—he even wrote a whole piece on it in 2014 for Rolling Stone) but

it’s a very surface level comparison; where Apocalypse descends into

darkness—Conrad’s heart of darkness—Z trends heavenward, achieving

transcendence. Both films have final stretches that go a step beyond what came

before them, but they’re near opposites in what they represent for their

respective protagonists.

[13] For example, his Benediction (2021),

which parallels Z’s war passages by being crushingly and unbearably

about the tragedy of WWI.

[14] A movie written by Edward Anhalt, who also worked on Edward Dmytryk’s The Sniper (1952), a kind of precursor to Fleischer’s film. (If you recall, Dmytryk later became president of USC and interacted with Gray during his time there.) Gray had planned to use the technique in another place too—behind Tom Holland when he tells his father they need to go back to look for Z—but apparently decided against it.

[15] A moment which came from a deleted scene that

was originally shot to go at the start of the film.

[16] Gray tells us that his eldest son is actually in this scene.

[17] Although via the turning up of a watch, which

Fawcett had said he’d send as a sign if he reached Z, Gray leaves open the

possibility of a hope that they made it. How to end a film about people who

disappeared, and who no one knows what actually happened to? In one of my

favorite, lesser known citings by Gray, he says he looked to the ending of Don

Siegel’s Escape from Alcatraz (1979) for inspiration.

No comments:

Post a Comment