THE GIRL OF THE GOLDEN EAST

On The Immigrant (2013)

The existence of The Immigrant in James Gray’s filmography posits the idea that one’s autobiography does not begin with one’s own birth, but in fact stretches back in time as far as one may wish to look. This has been a recurring thought in Gray’s cinema: that we are not only ourselves, but we are also the people, places, and events that made us—to go even further, we are the people, places, and events that made those people, places, and events, if at an increasingly smaller amount of influence, still nowhere close to zero. For Gray, this means that the story of his parents and grandparents is also the story of himself. In making The Immigrant, he called it “a process where I was trying to understand why my family is the way that it is, why our interactions are the way that they are.” A sort of psycho-historico-emotional examination of family history, if you will; a question of “how did I end up as the person that I am?” going back decades and decades before the birth of that “I”. A kind of prequel to the rest of Gray’s cinema, to Gray’s family, to Gray himself—what made him who he is, historically speaking. And this would be a complex continuation of Gray’s career-long drift from what is autobiographical to what is purely personal. The Immigrant, more than any Gray film to that point, would leave behind the surface autobiographical touches that had littered his filmography up to this point (a trend started in earnest by Two Lovers) and instead narrow in on something deeper, under-the-surface, things and ideas which touched Gray’s heart on the most intimate level. Ironically, this would be achieved through an autobiographical story—not his, though, but that of his paternal grandmother. (Even Gray confuses this point in an interview here and there, claiming it to be “his most autobiographical film” in one place and claiming the opposite in another; words are hard....)[1] Still, it slots neatly into his filmography as another of what he calls “small, intimate films in which I’m trying to uncover hidden aspects of my own identity.”

To see Gray make a period film is to see what was always hidden under his modern films, in which a sense of history existed that was so, so deep and veritably written on their surfaces (or as close to that as was possible while still remaining in the literal present.) In The Immigrant, the weight of history is put aside for history itself—something no less weighty. Set in 1921 in New York City’s Lower East Side, Gray’s first true period film[2] forces him to take up a new relation to his beloved New York[3] after having spent his career mapping a metaphysics of the city. Thrown back into an era of cultural changeover—the death of vaudeville and the birth of silent film culture—Gray has to conjure a new world. (He succeeds.) It’s telling that Gray’s working title for the film was originally Low Life; it’s a direct reference to Lucy Sante’s Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York (1991), a massive and massively entertaining work of cultural archaeology detailing life and politics in urban New York City from the 19th century into the 20th. Gray speaks of his love for the book, but it’s influence on the film is more spiritual than literal—the era Sante writes about ends just before the era Gray’s film takes place in, so he still had to do his own investigative work about the period. Gray spoke with Sante, but the idea of sharing a title was struck down—thus, we have The Immigrant (after a brief stint of being called The Nightingale, presumably a reference to the line in the film “the nightingale always sings sweetest at the darkest hour.”) It may be a century earlier but all the central Gray themes are transplanted: patriarchal families, class, etc. The uncle of Marion Cotillard’s Ewa, with his wife the only family Ewa and her sister have in America, becomes a constant threat after being told of certain shameful deeds Ewa may or may not have participated in on the trip over; her aunt (played in the film by one of Cotillard’s Polish coaches) is the more understanding and loving of the two, but any desire to help is overruled by her husband. The class aspect is too obvious to go into detail about—Ewa is literally a penniless immigrant, etc.—but the distance between the working poor and the leisurely rich is given an ironic visualization in a scene that sees Ewa and her fellow streetwalkers costumed and presented as the daughters of New York’s highest aristocrats.

As a period piece, The Immigrant plays almost like oral history cinema—except boosted into realms of beautiful cinematic art courtesy of storyteller and narrative magician James Gray. It’s worth telling, to the fullest extent I can, the real narrative history handed down through the generations that lies behind The Immigrant’s cinematic fictions:

Gray’s paternal grandparents, though from the same area—Ostropol, not far from Kiev to the west, in what is now Ukraine but was then Russia—came to the United States separately in 1923, via very different paths. His grandmother faced a violent catalyst for removal: while working in the family haberdashery in the Galicia region on Ukraine’s western border, White Army Cossacks invaded their store and beheaded her parents as part of an anti-Jewish pogrom. They died right in front of her; she was 16 years old. She came to America through Ellis Island, likely with her sister (as single women were not to be admitted). Gray’s grandfather took a more roundabout route. He had been forced into the army in Ukraine, but had been told, because he was Jewish, that he wouldn’t survive the night and should therefore get out while he could. Going AWOL, he made his way through Turkey and eventually wound up in South America[4] of all places, settling first in Buenos Aries for a time in 1922 before making his way to Ellis Island in 1923, thereby officially making him a South American immigrant in order to avoid any quotas on Eastern European influx. The two met at a Workmen’s Circle dance circa 1925 in Brooklyn, an event put on by the neighborhood Jewish community organization. (The event is referenced in Two Lovers, there as the way Leonard’s parents met.) Upon meeting they discovered that they came from the same city, and later married. His grandfather worked as a plumber for other Jewish houses throughout the depression years, setting up life for himself on Willoughby Avenue in Brooklyn, in the neighborhood now known as Bed-Stuy. Gray’s father, Irwin, was born in 1935. The family lived in Brooklyn until 1964, five years before Gray was born, when they moved to Queens. Both of his grandparents died in the early 1980s, but not before his grandfather took the 7-year-old Gray to the still-unrestored Ellis Island in 1976. His grandfather took one step into the place and burst into tears.

Gray’s grandparents spoke basically no English to the day they died, instead retaining Yiddish as their language. They never truly assimilated, and—to Gray’s befuddlement—waxed nostalgic for their homeland even with how terrible it had become for them there. But in here lies one of Gray’s ongoing themes: the idea that home will always retain some kind of gravitational pull on you no matter how poor that home land or home life is or was. The adult Gray regrets not being more receptive to his grandparents and their stories as a child, as who they were and what they felt—handed down to him through his father—would come to define much about Gray’s emotional state. Much of the sadness, loneliness, and melancholia that Gray has experienced can, for him, be traced via a straight line right back to his grandparents, emotional states of being and personality traits transferred from one generation to the next. The Immigrant is more or less Gray’s attempt to come to grips with that heritage, and it’s what allows him to make a period film that isn’t relegated to the past: “The point is to do something which, even though it is period, has a certain immediacy and desperation and drive that comes out of today, and that’s all about substitution. In other words, it’s all about making something that feels personal to you, even if it took place a hundred years ago.”

Gray says that around 80% of the film is based on recollections from his ancestors. On his mother’s side (which, like Ewa’s family in the film, is Polish) Gray’s great-grandfather ran a saloon/restaurant on the Lower East Side called Hurwitz’s (which is Gray’s mother’s maiden name.) A man named Max Hochstim, a local pimp, frequented the place there, and is the inspiration for Joaquin Phoenix’s character Bruno in the film. But for the emotional crux of The Immigrant’s story we have to return to that visit to Ellis Island in 1976 with Gray’s paternal grandfather; incredibly emotional himself, he noticed a woman crying and, after talking to her in Yiddish, learned that she had been separated from her sister on the island and had never seen her again. More than the simple facts of these stories, variations of which appear as part of the film’s narrative, it’s the emotional content of Gray’s ancestors and their experiences that make the film what it is; that is, a living, breathing historical recreation that swims not just in the atmosphere of the period but the emotional stirrings of the era’s hearts. And it’s around one of these hearts, that of Marion Cotillard’s Ewa, that there lies a locket which contains a picture of Ewa’s parents—the photo, significantly, is actually of Gray’s grandparents.

Much of the impetus for a reckoning with Gray’s family history came about via a serendipitous discovery: when his brother was moving from New Jersey to Pennsylvania in 2010, he discovered a large chest full of paperwork and photographs, a treasure trove of family history. Much of what they found were things they never knew about. Their grandparents had kept all of their papers from Ellis Island, along with photographs from their childhoods in Czarist Russia. Their well-documented family history was coming alive. Around the same time, their father moved from Queens to Manhattan and gave them some old photographic slides dating all the way back to 1949; they watched them together. More family history stuff was left behind for sifting through after the death of Gray’s Uncle Seymour in 2010 (if you recall, the same uncle who, upon hearing Gray’s desire to become a filmmaker as a teenager, had said “That’s a whole lotta nothing!”) Additional lore came courtesy of Gray’s great-aunt Sue on his mother’s side, who was full of stories about the Lower East Side and her experiences around Hurwitz’s; she only died at the age of 101 around the time of The Immigrant’s premiere.

Two or three other things would combine, in a spiritual mixture, that would lead to the conception of Gray’s movie. First is a night at the opera: in 2008, Gray and his wife went to the L.A. Opera (which he has a subscription to, and goes as often as he can) to take in a performance of Giacomo Puccini’s Il trittico (1918). The opera is a collection of three one-act operas: two tragedies and a comedy. At this showing, the two tragedies—Il tabarro and Suor Angelica—were directed by William Friedkin and the comedy—Gianni Schicchi—was directed by Woody Allen. But it was the middle operetta, Suor Angelica, which acted on Gray in such a powerful way that we might as well just say that, without it, The Immigrant may have never been made. “Unabashedly direct emotionally,” the convent-set drama about a nun seeking redemption moved Gray to tears for much of its hour duration. There was no wall between the story, characters, and viewer. He turned to his wife afterwards and remarked on how they don’t make movies like that anymore—the old Hollywood pictures with a female lead, like Barbara Stanwyck or Greer Garson, that were unashamedly emotional and direct. Gray’s wife suggested he make one; he agreed. In an era where they were no longer being made, Gray would return to the melodrama, to the “women’s picture”—one of the few avenues for the kind of pure, transcendent emotion that movies no longer trafficked in, but one which Gray had spent his whole career working alongside of under the guise of male melodramas.

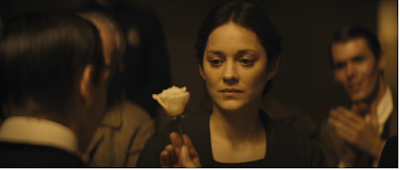

The Immigrant would be the first and to date only time where Gray’s main

protagonist is a woman. Gray found the perfect actress for the role essentially

by chance: he had been in Paris for Two Lovers and was told by a

publicisit that someone named Guillaume Canet (a French actor and filmmaker) wanted

to have lunch with him. Gray found Canet funny and they bonded for a time, and

then Canet said to come meet his girlfriend: Marion Cotillard, who despite

recently winning an Oscar for Best Actress was completely unknown to Gray. He

was immediately taken with her, and was struck by her silent film physiognomy:

she looked like Pola Negri, or like Falconetti in Dreyer’s The Passion of

Joan of Arc (1928), a face begging to be filmed. “When I knew she was going

to be in the movie, I already began framing her face,” says Gray. He explicitly

wrote the script for both Cotillard and Joaquin Phoenix; if they hadn’t agreed

to do it, he might not have made it.[5]

__

The James Gray-Guillaume Canet encounter—already fruitful in producing The Immigrant’s star performance by Marion Cotillard—also produced a side story to the James Gray universe that bears mentioning. Whether this was the real reason Canet asked to meet with Gray, or whether this came up in the midst of their burgeoning relationship, I don’t know—the point is Canet asked Gray to help rework dialogue into English for a script he had written for his next movie. Gray was in Beaune, France for a festival when he got a call from Canet telling him to come to Paris to help him, that he would settle him in and everything would be great. Gray agreed, but when he got there he discovered that Canet had yet to write a single line. He wound up staying in Paris for two months, helping him translate the dialogue (the French filmmaker’s movie would be his first in English) and also help structure the story a little bit. Canet insisted on giving Gray a co-writer credit, which Gray told him he didn’t need or want, forever giving the film’s appearance on Gray’s IMDb page more weight than it really has; apparently the actors improvised a fair amount while shooting anyway, so who knows how much of Gray’s work really ended up in the final film.

The film, titled Blood Ties, eventually premiered exactly

four days before The Immigrant, at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival. It was

a remake of the 2008 movie Les liens du sang directed by Jacques

Maillot, which actually stared Canet. The film isn’t a half-bad little crime

thriller with a few Grayian themes, a brothers-on-opposite-sides-of-the-law

story which plays out as a kind of inverse on the set-up in Gray’s We Own

the Night: where in that film the non-cop brother becomes a cop, in this

one the cop brother becomes a non-cop, even helping his criminal brother escape

from the police; though in opposite directions, both films see the estranged

brothers grow closer in a complex way. But the main draw here is that it’s a

field day for a handful of character actors: Clive Owen, Billy Crudup, Zoe

Saldana, James Caan, Mila Kunis, Matthias Schoenaerts, Noah Emmerich, and of

course also Canet’s wife Marion Cotillard. All of whom have done (two of them)

or could do (the rest of them) great work in a James Gray film given the

chance. My favorites of the bunch though are Crudup, Saldana, and above all

James Caan, who has a small role to really chew on and is given a couple

moments that are basically just excuses to show off his acting chops, which as

it happens are on par with anyone who’s ever worked in movies. (Edit: I wrote

these words about two weeks before Caan passed away at the age of 82; the truth

of it stings all the more truthfully now.) It may have started as a movie I

watched for the purposes of this project, but it became something that I was

simply glad I watched, straight up.

__

In a slight hiccup for the chronological auteurist who looks at the arc of Gray’s 2010s career as a neat, gradual distancing from his modern New York settings—from New York in the 1920s to the Amazon jungle to outer space—the script for The Immigrant was actually written after or concurrently with the scripts of those two movies. In fact, after being sent the book and signing on to direct The Lost City of Z in late 2008 before the source novel was even officially published, Gray was nearly all geared to go on that project; he had written the script throughout 2009 and had even made scouting trips to the Amazon jungle in preparation. But Brad Pitt dropped out as the lead actor and the financing went with him, leaving the project stranded for the time being.[6] The way Gray tells it, after setting that project aside, the script for The Immigrant came quick, writing it in just four weeks. Without definitive information here, it’s likely that this was in or around 2010 when this happened. The script for Ad Astra, alternatively, was written in 2011, as a break from attempts to get Z financed. So all three of these projects came into the world in the same whirlwind five-year period between the premieres of Two Lovers in 2008 and The Immigrant in 2013. As I’m not privy to any special informational access here, I can only guess at the exact timeline; in any case, The Immigrant started shooting in January of 2012 and wrapped up in March. The budget was around $16 million, much of the money apparently from French backers; Gray singles out Vincent Maraval, head of Wild Bunch, as instrumental in supporting the film’s production financially and otherwise.

The last little piece in the puzzle of The Immigrant’s conception is a beautiful accident of banal cinephilia: a random late night encounter with a film on Turner Classic Movies. Gray couldn’t sleep one night and tuned his television to TCM. What was playing but Federico Fellini’s La strada (1954), already a touchstone of Gray’s, except on this particular encounter it played for him like it had never played before—as very operatic, almost like a fable. Such is how the script started to take shape; family matters plus Puccini plus La strada, and with Marion Cotillard in mind’s eye as the actorly presence breathing life into it. Cotillard is essentially for Gray here what Masina was for Fellini, and, like we’ve already seen with Two Lovers, The Immigrant is unabashedly a variation on its double influence of La strada and Nights of Cabiria (1957). Parallel with La strada, Cotillard is Masina, Phoenix is Anthony Quinn; and Jeremy Renner is Richard Basehart, the holy fool playing rival lover against the mismatched beauty/beast relationship of the other two, the false hope that nonetheless represents something more beautiful in the world than shown by the other man. The structure is a total rip-off: Quinn/Phoenix, the brute characters taking the girl “under their wing,” while Basehart/Renner—the former an acrobat, the latter a magician—intrudes upon the narrative to the ire of the brute and the admiration of the girl. He’s killed by the brute who then ends the film in a fit of self-hatred and mourning, for who he is and what he’s done. The Immigrant only splits off from La strada in its last third, which may turn out to be significant(—we’ll see). Cabiria plays its role too, even if the ratio of Cabiria to La strada is slightly less here than in Two Lovers, whose ending was a transcendent variation on Cabiria’s ending-to-end-all-endings. When Cotillard gets dragged onto stage by Renner to be a part of his mind reading act, we recall Masina being chosen for an on-stage hypnosis in a scene from Cabiria—both end in the woman’s humiliation at the hands of a rowdy, seemingly all-male crowd.

Obligatory mention of Fellini aside, on The Immigrant more than ever Gray tried not to be influenced by other movies, at least consciously—the subconscious, Gray admits, has a will of its own. Beyond La strada, the only other movie Gray admits to watching in preparation is, interestingly, Robert Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971). (One look at the surfaces of the two movies side by side should answer the question of why.) He wanted the film to be its own thing, and he tried to move past other movies to the point where he didn’t even watch any; having been a pre-production ritual for the first phase of his career, we can point to this as a symptom of Gray’s new maturity, new confidence. Along with his continual move beyond genre—period isn’t really a genre, it’s really just a setting, and The Immigrant is really just the bland genre of “classic drama,” if not a new genre all-together (call it, I don’t know, cine-narrative opera)—but along with that, there seems to be a return to simplicity, something very primitive, cinematically, emotionally. My personal favorite of all the cinematic references Gray makes in interviews around this time is this nod to Charlie Chaplin:

At the moment, I’m rediscovering Chaplin with my children. What genius! I am stunned. Chaplin gives us the full range of emotions, from absolute pathos to the purest laughter. He makes us feel human. The script that I’m writing for Joaquin Phoenix is going to be very influenced by Chaplin!

The amazement of rediscovering Chaplin is something any seasoned cinephile should be familiar with. Pure simplicity, total complexity. We (me, Gray, and presumably you) point to the ending of City Lights, of course, as the ultimate example here. But in line with the melodramatic mode Gray traffics in, especially in The Immigrant, we could also mention The Woman of Paris (1923), an (unjustly) oft-neglected Chaplin-less* Chaplin that’s pure sophistication, pure melodrama, pure cinema. Just recall it’s subtitle: A Drama of Fate. And there you go—a working title for every James Gray movie. But of course the ultimate Chaplin reference is sitting right in front of our faces: The Immigrant (1917), the title of which has been stolen wholesale. It’s perhaps telling, cine-metaphysically, that while in Chaplin’s short film we get a shot of the statue of liberty head-on, a century later all Gray can give us is her back....

If we’re talking The Immigrant and other movies, it really doesn’t do much good to go beyond the 1920s and 1930s (outside of a few anomalies), so in tune the film is with silent and pre-Code poetics. There’s Griffith—Orphans of the Storm (1921) in particular, if we’re talking plot dynamics (the reuniting sisters); there’s Dreyer—the rapturous close-ups of Cotillard are this century’s version of Falconetti’s in The Passion of Joan of Arc; and there’s Borzage—maybe the most significant here as, knowing his unmatched ability for emotional transcendence, Gray’s mention of him comes as an almost impossible challenge, saying that with The Immigrant he wanted to make a film “that was so filled with sympathy and empathy for the characters, to out-Frank Borzage Frank Borzage.” Daniel Kasman has also perceptively written about the way the film teems with 1930s Hollywood:

This may sound overly poetic, and what is a bit amusing to me is that on paper The Immigrant sounds like a pre-Code potboiler: fallen dove new to the city oscillates between two men, one dark, the other light. Renner's odd character reminded me of a combination of James Cagney's stocky agility, a sense of dance, but also, dangerously, with Clark Gable's romantic rapscallion image, with charm to spare but paper-thin promises. Yet he's not nearly as well defined as either, existing like much of the film, somewhere in some middle. The 30s is a touchstone though, even though the film takes place in 1921. Cotillard reminds me so much of Sylvia Sydney, only profoundly sadder. Gray's cinema is so founded in 30s Hollywood cinema: ethnicity, life in the city, the conflict between family and society, a quick-fix American dream vs. older morality. Those stories were the default in those days, a dime a dozen.

While people continued to get stuck on Gray as some kind of '70s homage filmmaker, Gray was moving further and further backwards. As he continually said to his cinematographer Darius Khondji: “You know, sometimes to move forward, we have to look backwards.” I’ll grant a decent-sized '70s era influence; for example, the film is very much spiritually intertwined with the grand melancholy, albeit on a smaller scale, of McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Godfather: Part II (1974), Heaven’s Gate (1980), and Once Upon a Time in America (1984). But while swimming in the same aesthetic streams as those titanic films, Gray was off telling a smaller story out of some '30s Barbara Stanwyck melodrama. More recently, Gray has admitted that although while growing up his taste was obsessive about European cinema circa 1945-1980, nowadays he finds himself much more enamored with classic Hollywood cinema from the 1930s. Some kind of aesthetic redirection occurred; maybe one can partly point to the fact that around 2006 Gray stopped going to the movies with any regularity after having kids; maybe being forced to stay home led him to the usually relatively short, attention-grabbing, narratively gripping Hollywood films of the post-silent era. However it happened, this reorientation is visible in all of Gray’s 2010s work, albeit somewhat invisibly, as it happened at the same time Gray was coming into a new phase of his own artistic maturity.

With Two Lovers and The Immigrant, Gray says that he was getting closer and closer to “the cinematic expression of the mood and the attitude and the behavior and the feeling that I want to communicate.” With The Immigrant, however, there comes another break, or breakthrough: realism seeps away, and a mythic form only hinted at previously becomes explicit here—the film is austere, mystical; it glides. It glows like a copper plate etching, cinema preserved in amber. “My other films were meant to be naturalistic. You could always sense where the light was coming from. I abandoned that because I wanted to tell a fable.” A technical change, in addition to a philosophical one. The movie’s surface is full with that specific something—you know that luminous glow that ‘30s films sometimes have, particularly when it’s a close-up of an actress’s face? The Immigrant has that, except in color. The movie’s depths, simultaneously, are brimming over with... I don’t know what to call it, other than belief. A deep, abiding belief. For example, when Renner’s magician performs at Ellis Island, ending his show with a levitation act, the film believes it, as Cotillard’s Ewa does; this is not a trick, or an illusion—it’s magic. And from that belief—hope. Hope for Ewa in that moment—that she’ll be reunited with her sister before long—and hope for us as viewers of this magical movie—that, despite everything, something good will come of all this suffering on screen.

If this seems a bit naïve, a bit primitive, then so be it; for my part, I find it beautiful. Maybe as a culture we’re just no longer ready to give ourselves up to such an attitude, living in our oh-so-enlightened 21st century. But the Immigrant is everything we’re not: it’s the ultimate anti-irony anti-distance anti-snark anti-the-last-25-years-or-so-of-contemporary-culture work of art. Or as Gray remarked about his film’s placement in the 2013 Cannes Film Festival competition, it was him “trying to do Puccini in a field where they were all trying to do 1968.” It’s no coincidence that the film is set in the early 1920s, an era which saw opera die as a popular medium almost overnight and, out of its ashes, arise the silent film tradition—a tradition the best of which is verily unmatched in that beautiful, primitive naivety in which The Immigrant traffics. “I tried to have gesture—and this is, in a way, very much from silent films, very much from opera—to have the gesture inform the interior life of the character.” It’s a critical cliché, perhaps, yet it’s undoubtedly true here that one could remove all dialogue from The Immigrant and have it lose little of its power[7]; in fact, the dialogue as it is has a kind of clunky poetry to it that reminds one of silent film intertitles. But the film isn’t stuck in the era, idea-wise, as Gray assures us that he “tried to imbue the film with a certain complexity that might not have been present in a production from 1926.” Which isn’t to say that The Immigrant’s 2013 complexity is exponentially greater, on some timeline of eternal progress, or that the artists and audiences of 1926 are stupid; each era has its own emphases, and what one audience craves another doesn’t need; if a 1926 audience accepted archetypes, a 2013 audience demands nuanced character psychology; and for Gray, audiences can’t be ignored. Whatever way you look at it, 2013’s The Immigrant or any given silent masterpiece, neither is without that particular quality which qualifies them for eternal status—in the grand scheme of things, I could care less about their release dates.

I’m tired; let’s just let Richard Brody talk about the form for a bit:

... in a strange and entrancing way, The Immigrant fulfills a distant dream, that of Flaubert’s 1852 fantasy of “a book about nothing, a book without external attachments, which would hold together on its own by the internal force of its style.” The Immigrant, for all its meticulous detail and dramatic nuance, turns naturalism inside out. Gray proves—as he has always proved—that what matters isn’t frames and cuts, story lines and character traits, but the melodies and harmonies, the moods and tones that arise from them, and that, in turn, seem to deflect, distort, shudder, and shatter them.

Gray’s movie supersedes—as most good films do—the very notion of form. On the surface, The Immigrant channels the nearly oppressive solidity and narrative streamlining of the Hollywood movies of the late nineteen-thirties—the tightly strung studio mechanisms that Orson Welles would soon gleefully unwind and re-tangle. Gray renders classical cinema even more monumental and painterly than the works at its source, but the solidity of his frames is broken by the crude, indelicate, furious emotions under the surface. Only a fault line shows here or there, until there’s a tectonic explosion. Then the movie barely recovers its poise and lurches with a stifled agony toward its exalted, open-ended conclusion.

It's almost like the film’s style is its genre: the idea of calling its genre a cine-narrative opera like I did earlier is, I’m now re-learning as I write this, an idea sort of stolen from Gray himself. “I wanted to lose genre, to make something that was its own genre, an opera translated to a movie.” The post-genre aspect of The Immigrant, begun earlier with Two Lovers, is an important part of Gray’s maturation as a filmmaker, but it’s a part of his maturation that was really only possible to make at this juncture in his career. No producer would ever have allowed a just-graduated early-20s no-experience hotshot make a period no-genre “opera translated to a movie” movie, no matter how cheap. Getting work, and getting it again, required some kind of commercial context to put the money people at ease—genre. It’s totally fair to talk about Gray’s first three movies as explicit reckonings with the metaphysics of the crime/thriller/whatever genre, but a recognition of the economic necessity undergirding such reckonings is part of the picture. The Immigrant, by contrast, need not participate in any necessitated genre tradition, and can therefore simply be what it is. Now, this may backfire commercially, with little for an audience to grab onto in the way of genre signposts (granted, thanks to Harvey Weinstein, we never really got a chance to find out)—but on the purely artistic side of things, it’s a remarkable experience to behold this vision, like the unveiling of a new symphonic work by one of our greatest composers. As Darius Khondji relates in their making of the film, “we were more in tune with the music than with the images.”

Speaking of Darius Khondji. From the vantage point of 2022, now three films deep into their collaboration, maybe Gray’s most significant artistic partnership outside of Joaquin Phoenix. They had first met socially, and had then worked together on a commercial in Uruguay—yes, a commercial in Uruguay. Like many filmmakers, past and present (Fellini used to do it), Gray periodically does commercials in order to support himself financially, one, and two, in order to play with “all the new toys,” try them out, and see what filmmaking technology is available and/or desirable to have. It’s also a great playground to work with and learn from stellar DPs, like Khondji, as he did on a commercial for the French phone and internet service provider Bouygues Telecom which was shot in Uruguay. [8] They clicked right away, and Gray loved the way he worked; whereas “usually the cinematographer is hysterical about the conditions,” Khondji is “like Mr. Zen.” On The Immigrant and their subsequent feature film collaborations, Khondji’s relation to Gray is very much as what’s called a lighting cameraman; he lights the scenes with Gray’s input, but Gray chooses the lenses and where the camera goes. It’s a set-up more European than American, as American cinematographers tend to be more hands on.

But the collaboration was intense, Gray and Khondji two ends of a

wire vibrating full of ideas. While Khondji was in Italy shooting Woody Allen’s

To Rome with Love (2012), Gray sent hundreds of emails to him full of

iconographic references—paintings, photographs, etc.—along with explanations of

Gray’s vision and what kind of filmic images he was looking for. "He was

sending me signs,” Khondji says, “like he was slowly breathing the soul of the

movie into me. There was a subliminal emotional connection established: something

around redemption, about the soul.... They started to haunt me." The two

took countless trips to art museums, and then coordinated all their visual

research into developing, according to French journalist Samuel Petit, a “mood

board, a kind of impressionistic storyboard nourished by their research on the

film, with a list of shots next to the images put here or there depending on

scenes, characters, events....” Their visual references ranged far and wide,

everything from photographs of prostitutes to classical religious paintings.

Inspiration came from Lucy Sante’s book Evidence (1992), a collection of

evidence photographs taken by the New York City Police between 1914 and 1918,

as well as the photography of turn-of-the-century “muckraking” artists and social

reformers Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine. The latter’s 1905 photograph “Young

Russian Jewess at Ellis Island” was used as the basis for Cotillard’s look in

the film; for Gray, “her face meant so much to me—it was so evocative.”

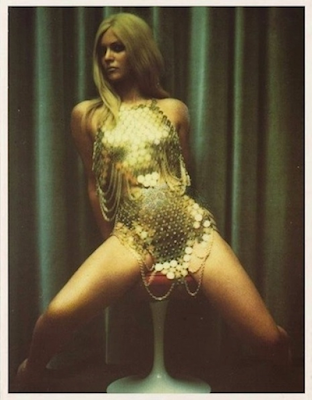

Two other photographic items were important in determining the film’s look. First, autochromes, or more specifically Autochromes Lumière—a color photographic process invented by the Lumière brothers in the first decade of the 20th century using transparent glass plates and mosaic patterns of microscopic color-dyed grains. Their unique color temperature gives the images an odd textural beauty; if I was feeling playful, I’d say their capture of color was to the spirit of the early 20th century what the beauty of consumer-grade digital video was to the spirit of the early 21st. Although there are few in the movie, Gray and Khondji particularly looked at them for daytime exteriors.

The other visual reference point comes from the Italian architect and artist Carlo Mollino, who between 1956 and his death in 1973 took hundreds of erotic Polaroids in his studio, a body of work that was never exhibited until the 1980s. Like the autochromes, Mollino’s portraits have a distinct color saturation and texture; the texture of these photos matched what Gray was looking for—a texture that was almost religious in connotation. As Khondji says, this texture to the image would be like a skin—“the skin of the film.”

From painting, Gray and Khondji drew from across hundreds of years of the art. From Caravaggio, as usual, whose blacks and earthy religiousness were a must for The Immigrant, all the way to the 20th century and the loose group of painters known as the Ashcan school. Everett Shinn and John Sloan, George Bellows and William Glackens, Robert Henri and Rockwell Kent. These painters captured early 20th century urban New York, particularly its poorer neighborhoods, with an impulse that was both documentary and impressionist. Gray’s color palette is nearly the same as these painters: yellows, browns, ochres, etc. Gray says that these painters “taught us a lot about the use of light, the direction of light.” It was paintings like these, rather than a supposed reliance on a lighting scheme inaugurated by Coppola or Leone, that inspired the lighting of The Immigrant. Plus the mere facts of the case: the lighting of the period, by gaslit lamps in an air full of soot, coal, and pollution, simply looked that way. The yellow-ochre hue of Gordon Willis or Vilmos Zsigmond’s work was unavoidable—they had gotten it right. Since I mentioned Zsigmond, the opening, England-set scenes from Heaven’s Gate (1980) were also looked at as a visual reference. All of these inspirations combine to create a filmic object which looks and breathes like absolutely nothing in contemporary cinema, and that’s intentional; Gray and Khondji even tried to literally bake the film in an oven for hours at a time, à la Gray and Savides on The Yards, but nothing they did had any effect—by this point, the film stock made by Kodak was indestructible. As Gray jokingly relates, “you call the Kodak guy and say the film stock looks perfect and he says Yeah, isn’t that amazing what we can do.”

(Three paintings are included for reference on the DVD of The Immigrant):

Gray was dedicated to getting his film looking a certain way, and this wasn’t just a camera/film task; it started from the very nature of the production and its design. Researching for the film, Gray became obsessed with the little historical details that would bring the film to life—“I remembered everything,” Gray says, “but just to be able to forget everything when shooting.” After finishing the script, Gray spent months hopscotching back and forth between his home in Los Angeles and to New York looking for filming locations. He visited both the Tenement Museum and Ellis Island dozens of times, both alone and with crew, and spent hours talking with the librarians at Ellis Island’s Bob Hope Memorial Library, who were immensely helpful. Gray had to do period on a budget, so location shooting—something he was absolutely dedicated to on Two Lovers—had to be mixed with studio work. So while he was able to shoot at the actual Ellis Island—for two days, or rather nights, since the Island was open during the day, meaning they could only work in the darkest nocturnal hours—much of the interior work was done at Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens (a place that Gray had worked at as a teen, where he first saw Gordon Willis at work.) Two Lovers’ production designer Happy Massee was back, and he created studio reconstructions for any stage work needing to be done, such as the theatre, which was based on a real place called the Haymarket. The costumes were done by Patricia Norris, one of the last films she worked on as she was then in her 80s, someone who had worked with many New Hollywood directors as well as being a longtime costume designer for David Lynch. The Immigrant also saw Gray’s first extensive use of CGI after the rainy car chase in We Own the Night—although you can hardly tell, since it’s used as sparingly as possible and for nothing outlandish; for this, he worked with the Brooklyn effects studio Brainstorm.

__

More than anything else, James Gray made The Immigrant under the sign of Puccini. Gray had already been making his own version of Puccini operas for a while, not least with The Yards which was specifically inspired by the Italian verismo movement, which we’ve already talked about back in that piece. If—as Gray reinvented himself in what we’ll call his second period beginning with Two Lovers—if we can consider Two Lovers a kind of Brighton Beach sequel to Little Odessa, then maybe we can consider The Immigrant a kind of Italian verismo sequel to The Yards. Gray calls The Immigrant “a verismo opera written for an actress.” The movie is probably as close as a movie has ever gotten to being an opera without being a literal filmed opera. Where opera and cinema depart (and where I think cinema has the ultimate advantage) is in audience distance; unless you have great tickets, the figures on stage remain out of reach, indistinct; in other words, there’s no close-up in opera. “I love opera for its very direct emotions,” says Gray, “they are there, on the surface, ready to be received. I like this frontality. It’s almost abstract. For its part, the cinema is more intimate.” Pure emotion, no irony or cynicism. This is of course in contrast to 99.9% of contemporary movies, and the sad, shallow state of contemporary cinema can be represented by this hilarious yet damning anecdote from Gray: “I had a meeting with another director, who shall remain nameless, and he said, ‘Who’s scoring you’re movie?’ And I said, ‘Oh, it’s all Puccini.’ And he said, ‘What other movies did he do?’”

The film is chock full of Puccini melodies, both real and fake. Composer Christopher Spelman not only rearranged pre-existing opera pieces, but composed what Jose Solís calls “a series of haunting melodies which both pay homage and carve their way from where Puccini ends.” Which is in its own way an homage to Nino Rota, who Gray says stole from Puccini greatly for the score of The Godfather. Strains from Manon Lescaut (1893) play over the opening black screen of the film, inviting us in to the story, setting the mood. From that opera, Act 1’s “Donna non vidi mai” is adapted throughout the score, as are strains of Act 3’s “Ansia eterna, crudel” which return at the end of the film. Further adaptations are included from La rondine (1917), whose Act 3 final duet becomes the love theme for Ewa and Orlando. (The name of that opera’s main character, Magda, is given to Ewa’s sister in the film.) We first hear this on Ellis Island, sung by Enrico Caruso, opera superstar of that era, before Orlando’s act. Gray knew he wanted to include Caruso singing at Ellis Island the second he found out that it had been a real historical occurrence. He asked around and found the most Caruso-esque opera singer of this day and age, and he was led to Joseph Calleja, who happened to have one day off on his busy schedule to come appear in the film. If you look carefully, you can see him being conducted by Christopher Spelman himself, playing Arturo Toscanini. Additional selections appear from Puccini’s La fanciulla del West (1910), among his most neglected works, and also his only one set in America. Its plot—a love triangle—has much that parallels The Immigrant’s. Caruso, who died in the year the movie is set, 1921, had sung that opera’s lead in its 1910 premiere at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, under Toscanini’s direction. From Mary Jane Phillips-Matz’s biography of Puccini we implicitly learn of an important thematic connection between the opera and the film: “In one of these [letters], the composer mentioned the word ‘redemption’ for the first time in connection with the opera. That, in the end, became its overriding theme and message. Drawing parallels between Puccini and Wagner, Michele Girardi brilliantly associates the importance of redemption in La Fanciulla del West with that in Parsifal, Puccini’s favorite Wagner work.” The Immigrant does also include some Wagner, as it were (in the scene where they’re being chased by the police). Additional music is also taken from Berlioz, Ravel, and Charles Gounod’s opera of Romeo and Juliet (1867).

If The Immigrant is an opera, then its actors are its librettists. Gray helped line them up with the rhythms of the movie, its melodies, literally and figuratively, by once again practicing his technique of playing music, especially opera, on set. For The Immigrant, he mentions Bach’s cello suites along with Puccini operas—Manon Lescaut, La rondine, and a lot of La fanciulla del west, an opera which Gray called “so honest about its cheesiness that it’s not cheesy, it’s just Puccini doing what he wanted to do. There’s a purity to the emotionality of it.” Gray has an intimate knowledge of opera, simply as a fan, and can discuss the pros and cons of different recordings of his favorite works; he even keeps a number of opera selections downloaded on his phone, always ready for instant playback. In regards to his penchant for playing such selections on set, on The Immigrant he went further than ever by literally bringing in a real orchestra to play music on the set: Gray had found a group called the Bratislava Orchestra, who for $1200 came and played whatever he wanted on set before shots. What this accomplishes on set is a kind of wordless emotional indication for the actors—in a way, the music becomes the director instead of Gray.

With the neutral state of the set already on high emotional awareness, it becomes natural for the performers to embody their roles in the mode of melodrama. Marion Cotillard’s character is like a silent film protagonist and a female opera figure put together; where an opera in some sense becomes about the voice of its soprano, The Immigrant becomes a movie that is about Cotillard’s face, as much as Dreyer’s Passion is about Falconetti’s. Gray says that he told Cotillard not to act. He didn’t even want her to be anything. He didn’t want her to play a character, or to create any boundary between herself and her character—she was only to be herself. But as much as Cotillard is clearly the film’s center, Gray had wanted The Immigrant to be about a co-dependent relationship (a concept borrowed from Alcoholics Anonymous), and Cotillard’s performance takes on even greater power when acting next to Joaquin Phoenix, whose twisted and faux-charming performance provides the other presence of overwhelming force. It's probably the most gravitational relationship in a Gray film between two non-related characters. Phoenix’s performance is also one of the most specific performances I can think of. His Rupert Pumpkin-esque emcee vaudeville act, acted as intentionally unfunny, pairs well with his forced charm that easily evaporates upon aggravation. As referenced by Gray, he’s part Fagin from Oliver Twist (1838), part Giancarlo Giannini from Lina Wertmüller’s Seven Beauties (1975). The forced formality, with a hint of actual charm, combine with his darker elements to create a character which Gray admits was much improved from their original, more brutish conception, and it’s all due to Phoenix’s casual actorly genius. Phoenix, who puts his whole self into the role, was disgusted by himself playing the character. He got so deep into the role, says Gray, that he was literally “anguished.” After one particularly good take of said anguish, him and Gray had this exchange: “‘Oh, that’s good. I like that you channeled that character’s self-loathing.’ He said, ‘Yeah, I hate myself.’ I said, ‘Yeah, yeah, the character’s…’ And he said, ‘No, I hate myself. I hate myself.’” He struggled with himself, fought with himself, and you can see it in the performance. So disgusted with himself, he would even go up to Cotillard after takes begging for forgiveness.

Second fiddle to the Cotillard/Phoenix relationship but in relative terms only, the Phoenix/Jeremy Renner relationship—here playing cousins—calls back to the male relationships at the core of Gray’s first three films and is another family aspect to The Immigrant beyond Ewa’s sister, aunt, and uncle. It’s merely hinted at in a few lines, but there’s history there; they were probably great friends as children and had a falling out. It resembles the Joaquin Phoenix/Mark Whalberg arc in The Yards (also cousins after a fashion), but with twice as much history and most of it offscreen. Just like Phoenix and Whalberg essentially fight over a girl in The Yards, sprawling out into the street in a chaotic brawl, here Phoenix and Renner are constantly at arms with each other, a sad violence that now defines their relationship and which causes things to end in a pool of blood, an accidental violent instinct performed as the result of a cruel joke—all over a girl. It took a bit to find Renner for the role,[9] but it’s a perfect fit and as far as I’m aware his greatest performance to date, and it’s a shame he, and so many others, haven’t gotten more work like this. His character of Orlando the magician was based on a real magician that Gray learned about, Theodore Annemann, who Renner resembles a fair amount. And he’s the perfect foil to Phoenix’s Bruno, a source of light for Ewa where Bruno is darkness, a kind of holy fool and yet someone all too human.

While Bruno pulls Ewa deeper and deeper into his selfish schemes (he’s long had the money to free her sister for her as promised, but just can’t let her go), Orlando represents the possibility of escape, of hope, of love—none of which Ewa can accept, because her love for her sister requires that she stay. It’s the push/pull of the American Dream: the opportunity is there, technically, but one’s obligations (practical, familial, moral, etc.)—often created by the very system which ostensibly offers the fulfilment of the dream—keep one from ever moving too far this way or that. Everything in its right place. The figurative imagery in The Immigrant is tragically on-the-nose: Ewa, dressed up in the garb of Lady Liberty, for a show in the very place which has trapped her, run by the very man that has ensnared her. We could say that the opening image of the statue is with her back turned to us—put more bluntly, however: she has been prostituted out. Ewa and her sister shuffle into Ellis Island with fear and anxiety, and nothing about the indifferent, systematic machine of the immigration process does anything to calm it. Finally making her way to an immigration inspector,[10] she’s just another soul lost in the rush of movement and the necessarily unfeeling process. But by the end of the film, with Ewa reunited with her sister and headed west, there is at the very least the possibility, if not the expectation, if not the implication, that they will “make something of themselves.” Or if we remember that Ewa is some variation on Gray’s own grandmother, maybe her ancestors will. Despite everything, despite Gray’s clear and ever-present skepticism (if not outright disbelief) at class mobility, there is still some small part of him that remains, deep down, American, and therefore a believer in this ideal. It’s in his very name: James Marshall Gray, named after Thurgood Marshall, the longtime United States supreme court justice. Up to this point, the American Dream has been nothing but a myth in James Gray’s films. But here, in The Immigrant, there is maybe, reluctantly, the recognition that it does exist, at least in some way. But it’s not a heel-turn; rather, it’s another piece of Grayian dialectics. It’s like what he’s said about The Godfather: Part II: “It both embraced and eviscerated the American Dream.” Gray’s very existence, as the filmmaker of The Immigrant, betrays his status as, in some weird way, an American success story: his grandfather a plumber in Brooklyn in the 1930s, here Gray is in 2013 with a film at the Cannes Film Festival.

__

The point is, how do you show love? I don’t think that can ever be an ambition. I think if you show, as much as you can, an honest depiction of our struggle and what it means to be a human being, then love is going to be part of the equation. – James Gray

James Gray is an atheist. He thinks that “the whole idea of God is silly,” at least on a conscious, practical level. But it’s remarkable the degree to which The Immigrant feels like—nay, is—one of the supreme religious works of our day. Part of this comes from the inspiring text: in Puccini’s Suor Angelica, the main character is a nun. Part of it comes from historical detail: by 1921, 98% of Polish immigrants were Catholic. Cotillard’s Ewa had to be a very religious character. The dramatic conflict of the film stems from this: asked to do something deeply against her beliefs, done in order to save another, there is inherently an inner conflict on an explicitly spiritual plane—more than even the conflict between Ewa and Bruno, the film is about the conflict between Ewa and herself in the eyes of God. The conundrum is partly inspired by Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, where a nun is told that she must sleep with someone if she wants to save her brother’s life. Ewa’s spiritual drama plays out most explicitly in the scene where she goes to church, where the religious atmosphere is overwhelming. What she attends is a traditional Candlemas service, a service highlighting Jesus’s presentation at the temple 40 days after his birth and the purification of Mary; the candles are a symbol of Christ, “the light to the Gentiles” from the song of Simeon. It’s in this scene that we’re reminded of Gray’s statement that he “especially thought of Bresson while preparing the film, in particular The Diary of a Country Priest [1951]” which he even stole a shot from, of Cotillard’s face surrounded by darkness as she enters the confessional booth, looking like a painting of the Virgin Mary. Gray says the scene is one of his favorite things he’s ever done. And it’s all scored to the monumental choral work that is John Tavener’s “Funeral Canticle,” famous for its place in another of the 2010s most profound religious works, Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011). The lyrics of it read thusly:

What earthy sweetness remaineth

unmixed with grief?

What glory standeth immutable on

earth?

All things are but shadows most feeble

But most deluding dreams

Yet one moment only

And death shall supplant them all

But in the light of thy countenance

Oh Christ, and in the sweetness of thy

beauty

Give rest to him whom thou hast chosen

Because thou lovest mankind

Gray’s interest in Catholicism can be traced back to his childhood. From a non-practicing Jewish family,[11] he was nonetheless fascinated by what can be termed ritual. He lived across from a Catholic school called Holy Family and would see the kids coming out of it, and the rituals on Catholic holidays. He was good friends with a number of Catholic kids growing up. The fascination continued, but his interest in Catholicism started mainly as a philosophical interest, only later growing into an artistic interest. He loved Renaissance painting and, in order to understand more about the religious symbolism, he would learn more about the religious history behind it. It’s really an artistic obsession—Gray’s real stance, like many other secular artists, is that art is his religion; cinema is his religion. In others this plays out in a shallow, unfeeling, faux-profound way; but Gray, in his unending empathy for his characters, almost takes on their beliefs in the making of the film. “It’s not the filmmaker believing in God, it was the reality of those people,” he says about The Immigrant. “I believe in God for art,” he says. Gray has always been a liturgical filmmaker, obsessed with ritual, but never more so than in The Immigrant. It’s almost like, for the film, for the duration of the production, purely in the role of movie director, Gray became a Christian. After learning about the near total prominence of Catholicism with Polish immigrants, Gray started reading St. Francis of Assisi; the Christian ideals of love and purpose distinctly color the film. Gray’s obsession here above all else is the Christian idea of love and redemption, and the idea of God giving meaning to everyone and everything—something that, even if Gray doesn’t actually believe, is extremely useful for Gray from an artistic point of view. Much of this can be traced back to a scene in La strada: Richard Basehart tenderly explaining to Giulietta Masina that everything—even the little pebble in his hand—has meaning, has purpose, has infinite purpose. Take that point and pin it on every human being, and we have one of the central themes of The Immigrant: despite one's suffering, nobody’s life is meaningless.

Or as Ewa tells Bruno, “you are not nothing.” Which Cotillard says with the anguished Phoenix crumpled up in self-hatred, embracing him in Gray’s second consecutive ending with Joaquin Phoenix being held in a sort of pieta variation. It’s hard for me to think of a more moving scene in all of cinema than this one: forgiveness offered by the sufferer to the one who caused her suffering. It may be a hard scene for some people to accept; there are few things more unfashionable than undeserved forgiveness, especially in a culture trained to heap hate and scorn on those who have caused suffering. Such forgiveness is irrational. Christian love is irrational. That’s what makes it beautiful. Without ever mentioning specific Christological points of theology, we have the heart of Christianity in this scene: undeserved love, unearned forgiveness, salvation from sins. Cotillard is Christ and we are Joaquin Phoenix. The forgiveness theme is foreshadowed throughout the film: in fellow prostitute Belva’s[12] forgiving of Ewa after she stole money, in the priest’s forgiving of Ewa after her confessional—now it’s her turn: the forgiven forgives. Bruno’s confession at the end mirrors Ewa’s in the church; where in the former Bruno is eavesdropping, in the latter Ewa listens with a loving and forgiving ear. Joaquin Phoenix tears himself apart, a scene so wrenching its almost hard to watch. “If you licked my heart you’d taste nothing but poison,” he spits—a line which Gray stole from Claude Lanzmann’s documentary Shoah (1985). It’s an agonizing moment, and therefore Ewa’s offer of forgiveness—her proclamation that he is “not nothing”—becomes all the more beautifully piercing. It’s an ending that recalls that of Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1865): a wretched man, saved by a woman who shows him love beyond what rationally makes sense. And it’s here where The Immigrant again parallels Puccini’s La fanciulla del West, and the passage in it that proclaims “the road to redemption is open to every sinner in the world. May you all hold in your hearts this supreme truth about love.”

Every sinner in the world. That includes Joaquin Phoenix’s Bruno; that includes me and you; and that includes James Gray. If you read enough interviews around the time of The Immigrant, you’ll come across a couple of very vulnerable moments from Gray that immediately reveal themselves as the secret heart of the movie.

So there is a difference between the surface of the film and what’s at the core of the character, and I identify with both of the main characters—with Ewa and Bruno—very directly. I mean, I’m filled with self-hate. I cannot stand to look at pictures of myself, to read things I’ve said, to watch myself. It’s embarrassing. I mean, I look like a complete jerk! That feeling of self-hate, which is not the same thing as self-pity, by the way, is personal. It’s autobiographical and I put it into both characters. It’s the way into the story for me. The rest is really window dressing. Usually, the conversations I have about the film are about the fact that it’s set in 1921, that it was shot at Ellis Island, and that’s all good, it makes me happy, I love that stuff. But it’s not the reason I did any of it. The reason I made the movie is I wanted to show a co-dependent relationship that sort of destroys two people, even though they need each other. They need each other for the wrong reasons.

And with that character I felt a close kinship, you know, obviously I’m not a pimp in the Lower East Side... but what I can say is that I did empathize with his self-loathing and his struggle to survive, his struggle to battle... in my case, depression... but certainly to battle the difficulties of living.

So when we talk about this film… I guess I had been beating myself up for a long time, about one sin or another that I had perceived that I had committed. And I guess I wanted to try and say to myself and to others that, no matter what you do in life, there is the possibility of redemption. And forgiveness. And that nobody is garbage—nobody is beneath us. This idea of being condescending to this character, or condescending to anybody, is almost a cancer.

There are things that I've done in my life that are flat-out awful, and I'm totally ashamed of them, and I'm sure that's the case with every human being that's ever walked the earth. The degree to which you're able to convey that that is okay—that you can't keep beating yourself up over the dilemma in which you find yourself—that what we are about is a process, it's a lifelong challenge to be what you might call a good person. The specter of forgiveness and redemption is always around the corner, no matter how terrible we may be.

Gray—facing depression, self-hatred, beating himself up over past

sins, you name it—made a movie. A movie more personal than I think, perhaps, it

is even possible to understand. Essentially, James Gray gathered up dozens and

dozens of people, millions and millions of dollars, years of research and writing and filming and editing, all to

offer *himself* forgiveness. He is forgiving himself via his own film.

Almost like he made the film to purge his own guilt. On the one hand, it’s the

ultimate act of artistic narcissism (a quality Gray has repeatedly admitted to

not only having, but needing, as a film director); but on the other hand, by

making a film to forgive himself, he was also, simultaneously, making a film

about learning to forgive others. Forgiveness and love—this doesn’t stop

and start at Gray, but rather flows out to the characters, to the viewers, to

everybody. This art of self-therapy becomes, via this personal specificity, an

art of universal edification. So by being so much about James Gray, it becomes

so much about you, about me. I would never publicly speculate about what sins

were haunting Gray; it suffices to think about the ones that haunt oneself. And

then from an honest consideration of oneself—outward. To others. Any honest

reckoning with oneself will necessarily lead one to be more forgiving of

others. Gray: “We should not make judgements about anybody and that’s the whole

point of it, to leave an eternal mystery at the heart of everybody.” In this

way, there is expressed an all-encompassing (specific) love that looks from

others to oneself and back again and says: we matter. It’s this theme of

love that is really, implicitly, the very heart of all of James Gray’s work to

date—the extension of sympathy, empathy, forgiveness, love, to every single

human being, all flawed, but, by virtue of their humanity, worthy of human

kindness.

__

And I haven't even mentioned the actual final shot, which if you’ve seen it I don’t even need to post an image of it because it will surely have been locked in your head ever since you first saw it. The ending here parallels that of Two Lovers: not vague, perfectly clear, and yet so complex and ambiguous in a way that no articulation can untangle. Two feelings, two situations, exist simultaneously—except where in Two Lovers both of these feelings existed in the one person of Joaquin Phoenix, here they exist separately, in both Cotillard and Phoenix, headed in opposite directions—and yet by the magic of the frame, they appear to be heading the same way, a testament to the complexity of the bittersweet ending: it appears that the bitter part is confined to Phoenix and the sweet part confined to Cotillard, except it’s not that simple, because he’s been forgiven and she’s no longer pure. Nonetheless, with Ewa and her sister unequivocally together, united, heading the same direction, we have Gray’s most optimistic ending of his career up to this point (something I’ve said about the last two films, and, spoiler, something I’ll say about the next two, too). Or if it’s not optimistic, it’s at least non-tragic, and moving towards optimism, in the arc of Gray’s career. At the end of Two Lovers, Leonard’s plans to run away to California with Michelle fall to ruin; here, Ewa and her sister are actually on their way there—it’s progress. This newfound optimism reflects Gray’s changing worldview; a change that Gray chalks up to having children (at this point, he now has three).

It's a lot more anxiety, constantly being worried about them, but having children fills you with a very profound love. It has been tremendously rewarding and moving watching them grow up. I hope that it will add a more hopeful ingredient to my films, because in all candour, I think that's a flaw in the work. Not with The Immigrant though, I feel that's there's a sufficient tenderness and hopefulness at the end.

The Immigrant reflects a lot of darkness but also an understanding that maybe life isn't all terrible, and that at some point you have to stop fighting the current and simply do the best you can.

Whatever bleakness Gray’s first films were drowning in has

disappeared: the honesty about the darkness is still there, but it's cut through

with a profound love, tenderness, and hopefulness that the Gray of 24 didn’t

have, but which the Gray of 43 does. It’s progress, and—if one is invested in

the filmmaking career of this man as much as I am—I think it’s quite moving.

[1] To put the autobiographical/personal

distinction to bed for the remainder of this post: autobiographical = facts,

personal = what matters to you, what you care about, what you are trying to

communicate.

[2] While technically period, We Own the Night’s

late ‘80s setting is too palpably close to us to feel like true period (in

my opinion); my arbitrary distinction is that for a film to be true period the vast

majority of people alive at the time of the setting have to be dead.

[3] Around this time, Gray was in the midst of a

new relation to New York City in real life; having lived in L.A. for seemingly

most of his post-collegiate life, coming back for long stretches to make

movies, he would like to move back for good—but a sketchy relation with Queens

and a now unaffordable Manhattan means, to him, that he has been pretty much

kicked out of the city.

[4] I can’t help but speculate on this piece of possible

deep lore within the Gray filmography: could James Gray’s grandfather have

crossed paths with Percy Fawcett?

[5] Ric Menello, Gray’s co-writer and collaborator again after Two Lovers, claims that Gray was considering casting Mark Whalberg instead at one point, and that he (Menello) pushed for Phoenix; he says that once the character was changed from a kind of brutal mob enforcer to a pimp, it became a no-brainer who to cast.

Menello died on

March 1, 2013, about a month before the film was officially finished, but he

did get to see it before he passed. Gray spoke about him in an interview: The

movie is very personal to me. And it was the last film I was lucky enough to do

with Ric. That was a great part of the experience. Now that he's gone, and the

movie is over, I have to let go of it, and it's not that easy for me to

do. I loved him profoundly and spoke to him for hours every day. There's really

nobody I miss more. I think about him constantly, almost like I want to reach

for the phone and call him, but I can't. I just keep hearing all the times I told

him to go to the doctor in my head. He would tell me ''I have problems with my

chest.'' I'd say ''You have to go to a doctor. I'll have a car pick you up.

Don't worry about the money.'' But he would never go.

[6] I’m choosing this as the place in which to drop all known information about James Gray projects that were reported as happening and then never did, at least not yet (and I doubt ever will):

c. 2010: Gray’s

name was attached to a project about Miles Davis with music by Prince, with a

shoot planned for 2010. Was never made.

2010: Not a

project Gray was going to make, but a project that Gray did a rewrite on (which

he doesn’t usually do) is Vlad, a film that was being developed by

Pitt’s Plan B company for Charlie Hunnam (this ironically a few years before

Gray had ever met him).

2011: An adaption

of The Gray Man was to be made with Brad Pitt, and later Charlize

Theron, but it stalled out and was later picked up by the Russo brothers and

was released as their movie this year with Ryan Gosling. Gray’s vision for it

would have been a kind of expansion of the We Own the Night car chase:

“Almost every shot was from Joaquin’s point of view, inside that car, and I

want to make a whole movie with that POV.”

c. 2012: Jeremy

Renner was developing a biopic of actor Steve McQueen that Gray wrote a

screenplay for, which he might direct as well. “I got into it very seriously. I

was spending a lot of time with Steve McQueen's ex-wife and sort of started to

live the Steve McQueen thing and began to really get involved with the subject.

And then I realized I can’t get so attached.”

2013: Gray signs

on to write and direct White Devil, a Boston-set crime drama for Warner

Bros. “A contemporary drama centered around a white orphan who is adopted into

a Chinese family, and eventually rises to the top of the Chinese Mafia in

Boston.” Gray had said in 2014, “It’s a similar theme I’ve played with before.

A guy rejected by his own who did everything he could to fit in elsewhere even

though it was illegitimate.”

2018: Gray was

(is?) set to direct the “terrorism thriller” / spy movie I Am Pilgrim, an

adaptation written by the book’s author, for MGM. “A former spy is called up

out of retirement to assist in an unusual investigation,” per IMDb.

[7] A fun anecdote from Gray, about something William Friedkin once

said to him: He told [my wife and I] a funny story once, which I told to

Darius before we started shooting. They were playing The Exorcist on

a sheet in Thailand, and a guy would, every 10 minutes, stop the projector,

walk up to the front and say, “Okay, in the last 10 minutes, here’s what you

saw.” And he would translate. And then, they’d start the projector again. Then

in 10 minutes they’d stop and he’d get up. And Friedkin said, “My job as a

filmmaker is to try and put that guy out of business.”

[8] Gray also did a few commercials with Harris Savides. Although I highly doubt this is comprehensive, I’ve attempted to make a list of all the other commercials Gray has done that I can find on the internet. I’m including links, but I neither expect nor really recommend anyone to click on them:

2013: an ad for Martell XO cognac, with Khondji behind

the camera.

2013: an ad for Citroën, with Ewan McGregor and Gray alumnus Vinessa Shaw.

2015: apparently

a sequel to a 2010 Scorsese commercial, an ad for Bleu de Chanel.

2016: a fashion ad for Lancôme with Julia Roberts.

2019: an ad for Taco Bell, done with Hoyte van Hoytema and explicitly based

on Ad Astra.

2021: an ad for the New York Lottery.

[9] Casting rumors again coming from Menello, who

was often influential in that department; he tells us that at first Matt Damon

was interested in the role, but as he was working on directing his own film at

the time (2012’s Promised Land, directing duties later handed over to Gus Van Sant), and the insurance people didn’t want

him flying back and forth to shoot Gray’s film on weekends, he couldn’t do it;

Robert Downey Jr. was considered but wanted too much money; James Franco,

although a fan of Gray’s, was in the running but his reputation had apparently been too

damaged by his poor co-hosting experience at the 2011 Oscars; Josh Brolin was

interested too; but they eventually realized that Renner was the right fit.

[10] ... played by Antoni Corone, who was one of

the main cops in We Own the Night.

[11] Much of the religious dimension of Gray’s cinema can be explained with reference to the combination cross/Jewish star worn around the neck of Vadim in We Own the Night; culturally Jewish, artistically Christian, in reality non-practicing of either—an atheist. We see both all over the place: the Jewish families in Little Odessa and Two Lovers, the implicitly Catholic families in The Yards and We Own the Night.

It may be worth

noting that it sounds like a fair amount of the Catholic material in The

Immigrant was written by Ric Menello.

[12] Which is also the name of the girl Joaquin Phoenix brings as a

prospect for Mark Wahlberg in the first scene of The Yards, in case you

were looking for an in-all-likelihood meaningless connection.

No comments:

Post a Comment