L’ARRIVÉE D’UN TRAIN EN GARE DE QUEENS

On The Yards (2000)

The cinema/train connection needs no introduction. The fact that

one of the first films ever projected to an audience was of a train entering a station

exists not simply as a historical footnote, an interesting trivia fact, but

rather as a genuine and mysterious point of metaphysics in the history of

cinema, something the mere reference of, implicitly or explicitly, opens a tiny

secret corridor of edification and rapture for the seasoned cinephile. So to

point out the fact that James Gray conceived of The Yards exactly one

century removed from the projection of L’arrivée d’un train en gare de la Ciotat

on a sheet in Paris, automatically adds a specific strain of significance

and accidental beauty to the film’s proceedings. Not to mention that the film

itself is about trains in a way movingly inverse to the Lumière film: instead

of looking at them face-to-face, The Yards gives us the backside of trains,

so to speak; we’re not really dealing here with the poetics of passengers and

crew boarding, riding, or disembarking, but rather with the secret workings and

shady dealings that make up the trains’ behind-the-scenes existence. Rather

than a shot of a train coming towards us, the first Lumière-esque 50-second snippet

The Yards gives us is a shot from the train looking backwards, the train

not even visible.

The opening shot is one of the all-time great moments of banal cosmology in cinema: contextless, we see dotted points of light slowly whipping past our receding point of view—it predates Ad Astra as our first view of the stars in Gray’s cinema. Caught accidentally by a crew member who had turned on the camera earlier than needed, its very existence is a little poetic fillip of fate. A glimpse of something abstract before opening up on the light of day in the thuddingly literal environment of Queens, New York. The train carrying Mark Wahlberg into a story that’s structured, tragically, to send him right back the way he came. The film will exist as little more than a two hour glimpse at this character and the way the world works against him. But in the meantime, we come to love him; and what the world can’t give him comes to stand in for what the world can’t give us. And in our dual struggle against the titanic obstacles involved in living, we reach some sort of shared catharsis that could be summed up like so: this is reality, and we must all partake in it.

__

The post-Little Odessa (1994) years introduce us to one of the (unfortunately) recurring aspects of Gray’s early career: the time between films will be much longer than desired. This is due to a number of factors but central to them all, and most significant for understanding Gray as an artist in a system resistant to that artistry, is the simple fact that he wanted to make the films that he wanted to make. The script for his eventual second film, The Yards, was started almost immediately after Little Odessa had premiered, and it was too close to his heart for him to be anything other than obsessed with making it—this one film and this one film only. When it finally came out (barely, and one major creative fiasco later) it was as though the world was seeing something from another era, both literally—the film was shot in the summer of 1998 but only seen after the turn of the millennium—and figuratively: Gray and cinematographer Harris Savides had explicitly set out to make something that “looks like somebody made a movie in 1971 and they lost it and then it got restored and showed thirty years later.”

Those six years were a long wait; and for more than a part of the time it wasn’t just a wait but a fight. Little Odessa had nabbed enough critical success (if not box office) to make Gray a decently hot up-and-coming prospect for studios looking to get their scripts made. Planted in L.A. and living cheaply in order to more easily remain unmoved by financial offers, Gray determined to hold his ground until an opportunity arose that tickled more than just his pocketbook. At one point he even authored a script based on the Philip K. Dick short story “Paycheck” in order to make ends meet. One source also places him teaching some filmmaking classes to UCLA freshmen. Gray finally signed a development deal with Fox Searchlight, a two picture deal, where The Yards would first get off the ground. But before Gray had finished writing The Yards and set out to get it made in late 1996, he was being sent script after script that the studio wanted him to do. (One of these was eventually made by Alan J. Pakula in 1997, with Brad Pitt and Harrison Ford, as The Devil’s Own.[1]) But The Yards wasn’t to remain at Fox; as fate would have it, a series of executive shifts at the studio sent the script into turnaround and it was picked up instead by Miramax—the company run by the brothers Weinstein. Paul Webster, producer on Gray’s first film, had become an executive at Miramax and got Harvey Weinstein to pay attention to Gray’s project—Weinstein, also from Queens, loved Gray and his depiction of New York. Little Odessa producer Nick Wechsler also came on board, and the film was on its way to getting made to the tune of a $17.7 million budget.

Gray’s first few drafts of The Yards were coming in at around 200 pages; Weinstein insisted he focus it to get down the length. Struggling with the structure of the thing, Gray asked to bring in outside eyes for assistance in the form of Matt Reeves. The two close friends had met at 18 in film school and worked on each other’s thesis films; Reeves’ great debut film The Pallbearer (1996) thanks Gray in the credits, as many of Gray’s films do for Reeves.[2] The script had originally been structured as a Rashomon-like narrative splintered into five different points of view, all centering on the trainyard incident that sets the film’s narrative in motion—an idea that wouldn’t be abandoned until the editing stage, when things were refocused around Wahlberg. But with Reeves’ help the script was in good enough shape to shoot; which meant it was in good enough shape to cast.

The triumvirate of young actors—future stars, but at this point still early in their careers—all came to Gray rather than he to them. Joaquin Phoenix, the lode star of the middle of Gray’s career and no doubt his most important collaborator to date, was only made aware of the film by accident. Weinstein had sent the script to Liv Tyler, who, as it happens, Phoenix was dating at the time after the two had met on the set of Inventing the Abbots (1997) (and who would eventually work with Gray as well decades later); he got his eyes on it and immediately had his camp reach out to Gray. They met at a restaurant in New York in the winter of 1997, and after already having met with hundreds of actors, Gray finally met one who wasn’t lacking the qualities he was looking for in an actor. He had first seen him in Gus Van Sant’s To Die For (1995): “I really liked his face. It immediately made me want to film it.” At first, Gray wanted him for what would eventually be the Wahlberg role (and had originally reached out to Benicio Del Toro to play Phoenix’s eventual role before the actor ultimately didn’t want to do it); but Wahlberg had reached out as well and aggressively campaigned for the role, thinking himself the perfect fit (and rightly so). Both, incidentally, were casting decisions resisted by Weinstein.

Gray had first clocked Wahlberg in his supporting role in The Basketball Diaries at Sundance in 1995, and Gray’s friend Paul Thomas Anderson (they had met in the early 90s and as a curious historical note saw Pulp Fiction in theatres together) showed him some scenes from Boogie Nights (which hadn’t been finished yet) to give him an idea of his talent. To complete the trio of young soon-to-be stars, Charlize Theron also called to participate herself. The trio of older, established actors were whittled down from a few circling options: James Caan, himself a Sunnyside Queens native, eventually landed the role after Robert De Niro decided he didn’t want to do it (and Sean Penn, originally looked at for the Wahlberg role, followed suit). Both Gena Rowlands and Ann-Margaret were in the running for the roles of the two older women, but former New Hollywood starlets Ellen Burstyn and Faye Dunaway eventually took the parts.

Filming finally got underway in the summer of 1998 in the form of

a 59-day shoot, and Gray delivered a cut of the film in September. It would be

almost two years until the film would properly* see the light of day.

__

....so to return to those trains—

The Sunnyside, Queens setting is what it is, the whole film shot on real locations. Save for the Handler apartment, that is, which was constructed on a stage and explicitly modeled on an idea of the apartment in Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis—long, claustrophobic hallways, a mood of decay, and a bedroom set across a chasm from the living area, loneliness set apart from warmth. Wahlberg is the film’s Gregor Samsa, a young man who just wants to be a productive member of society but whose honest attempts at doing so is thwarted by something beyond his willpower; where Kafka’s short story locates this in absurd and very much banal horror (simultaneously a metaphor and not one, just a slow decay and a cutting off from life and family), Gray uses the absurdity and banality of real life, pitched naturalistically rather than fantastically, as the unavoidable environmental handicap placed on Wahlberg’s character which leads, gradually and unstoppably, to his societal “death,” in the eyes of both himself and greater society; the dead look in his eyes, back on a train to nowhere, is as much of a death as Gregor Samsa’s.

If the real life train element comes from the autobiography of the father, the fictional locus point is La bête humaine, and the twinned influence of Emile Zola (novel, 1890) and Jean Renoir (film, 1938). To start simply, the three-point parallel comes courtesy the combination of Zola’s naturalistic fatalism, Renoir’s atmospheric romanticism, and the story itself, with which The Yards shares more than a few plot elements: the prevalence of trains (the opening shot an accidental rip-off of an early shot in Renoir’s film), an aborted murder, and the death of the lover at the hands of the lover, to name just three. But the main character, Jacques Lantier, played by Jean Gabin in the film, can be found in both the Wahlberg and Phoenix characters of The Yards. The aborted murder (of Lantier’s attempted dispatch of his lover’s husband) is given to Wahlberg (pushed into an attempt to kill the cop who accosted him at the train yards); the death of the lover (Lantier, overcome with a fit, kills his) to Phoenix (accidentally killing his fiancée Theron in a fit of Othellian rage).

More to the point however is the stylistic and philosophic carryover from text to film to film. Zola, the Naturalist par excellence, can’t exactly be found in The Yards in his full form; the harsh, plain reality laid down on paper in writing has been filtered by its entrance into the cinematic domain, not once but twice. Renoir’s poetic realism, as much as it might herald the neo-realism of the next decade, is still very much concerned with poetry over any hardheaded adherence to ‘the real’. Andre Bazin called it Renoir’s “simultaneous expression of the greatest fantasy and the greatest realism.” (The Yards could certainly be seen, as many of Gray’s films can, as participating in a tug of war between various variations on cinematic realism throughout the medium’s history: French poetic realism, Italian neo- and especially post-neorealism, and the American neorealism of the 1970s.) So The Yards is more than naturalism but less than poetry, and yet not strictly realism; it sits in its own unique wedge of cinematic history. Call it, I don’t know, poetic urban neorealism. Where reality meets story meets art, or what Gray calls his “eternal variation of Shakespeare crossed with Zola.”

So as he flirts with and floats amidst multiple ideas of realism

with the film, at the same time Gray is creating what can only be considered

artifice: a story structured to elicit a specific emotional reaction, accomplished

with images of explicit surface beauty. In other words: opera and painting.

__

It’s no secret that The Yards also exists under the sign of Luchino Visconti in general, and Rocco and His Brothers (1960) in particular. Visconti, the aristocrat obsessed with class, worked under Renoir on his proto-neorealist masterpiece Toni (1935) before entering the big leagues himself. Ossessione (1943), La terra trema (1948), and Bellissima (1951) are all touchstones of post-war Italian neorealism after a fashion, but the “genre” was falling apart almost before it got going, and maybe never even really existed at all.[3] By the time Visconti’s color masterpiece Senso was released in 1954, the Italian cinema had settled into something more comfortably itself, where the spirit of neorealism lived on but each filmmaker—Rossellini, Visconti, and the new director on the scene Fellini—followed their own proclivities towards a realism less real. Visconti, for the next twenty years, kept pulling his particular thread and never stopped; fantasy, opera, and historical grandeur overtook any specific dedication to proletarian realism (although the nearly three hour La terra trema’s sweep is closer to what Visconti would “become” than any other neorealist film I’ve seen, so this is all really less defined than the film history books make it out to be.) Maybe the most essential demonstration of where neorealism would end up is Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers, released fifteen years after the end of the war, a spiritual remake of La terra trema but full-on operatic in its gut-wrenching force where the previous film had worked a more subdued if similarly chilling effect.

But it’s still essentially a tale of a family, of brothers, trying

to make it work in a country set up to keep them down. The Yards is this

too, and if the world of this film is smaller (its runtime, too) its cosmology

is still as wide. Just compare the two fight scenes, the latter freely and

admittedly ripped off from the former, of Alain Delon and Renato Salvatori in Rocco

and of Mark Wahlberg and Joaquin Phoenix in The Yards. Both are set

off by violence towards women—the rape of Annie Giradot, the slap of Charlize

Theron—and then spill into the streets where the brothers (literally in the

former, figuratively in the latter) fight each other under the cosmic gaze of

the camera lifted high above, in tragic long shot. These are climactic scenes

of silence, God’s-eye views, that reveal at one and the same time the intensely

confused feelings of the characters towards each other as well as the intensely

tender feelings of the filmmakers towards the characters. The heart breaks,

that the love of brothers should turn to hate.

And with that we’re back at Dostoevsky, as touched upon in last week’s entry in the chronicles of James Gray. But this time let’s mention Dostoevsky’s less remarked upon masterpiece The Idiot (1869), the central love triangle of which, differences aside, forms the essential basis for those in both Visconti and Gray’s films. Prince Myshkin and his friend Rogozhin and the woman between them, Nastasya Filippovna. Myshkin’s holy fool status adds an important theological wrinkle mostly absent from either of the two films, but the structure remains similar. We have our “innocent” character (Myshkin, Delon, Wahlberg) who in one way or another loves the girl (Nastasya, Giradot, Theron), who is also loved by a “brute” character (Rogozhin, Salvatori, Phoenix) that’s the friend/brother of the other male in the equation. The shared tragedy is that in the end the brute kills the girl, and this serves as the climactic cathartic release of all the knotted relationships and passions up to that point. Our “innocent” is more or less sent back to where they came from, a cycle of violence completed in a society where any goodness must be snuffed out before it can do too much damage to the way people live.

In both films the overarching tenor of the piece is operatic tragedy; an important tradition for Visconti, who grew up rubbing shoulders with Arturo Toscanini and family at La Scala and would have a long career directing operas parallel to his film career. But it’s arguably just as important a tradition for Gray, whose films swim in the operatic tradition and share their emphasis on emotion, atmosphere, storytelling, and more.

Occasional trips to the opera in Gray’s youth were mostly unsuccessful in leaving their mark. But Gray was struck by Franco Zeffirelli’s 1982 film of Puccini’s La traviata at age 20, and finally fell under the operatic spell around the time that he was editing Little Odessa. His brother, Edward, had been listening to tenor Luciano Pavarotti’s recordings of Verdi’s Rigoletto; Gray became interested, and bought himself a CD of Verdi preludes done by Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan. The most important discovery came a little later, a year after the release of Little Odessa, and “an aesthetic shock”: the work of Giacomo Puccini. Gray had met his artistic counterpart of a century earlier, and it was a match made in heaven. Puccini had been the masthead of the verismo tradition in Italian opera, a turn of the century artistic movement (paralleled by Zola in literature) that took working class protagonists and treated them as though royalty, creating epics for the common man aimed towards the new audience for operas; at this time, operas were not an “intellectual” medium reserved for elites, but instead essentially played the role that cinema had in the golden age of Hollywood—the popular medium of the time.

(Following the truth of this, it perhaps shouldn’t be a surprise that the bourgeois critical class of America found little of value to say about The Yards and totally missed out on recognizing one of the country’s greatest film artists; á la verismo, the film is for the people that it’s about: the working-class, which over the following decades would fade even more from the cinematic spotlight that it had held in, say, the '30s and the '70s, my picks for the two most important decades of American film history when talking about the work of James Gray.)

It shouldn’t be forgotten that Gray’s inspiration from Italian opera rivals the place of Italian cinema in his work, and in some ways exceeds it. Opera, and of course music in general, indeed plays a role arguably just as important as anything strictly cinematic. Following a tradition dating back to the silent era, Gray even plays music on his sets while shooting:

I had done a little bit of that on Little Odessa. I think I read about von Stroheim doing that, or someone else from the silent era. It became a very time-honoured tradition in silent films for the director to play music on set for the actors and inspire the performances. Then I read that Stanley Kubrick had done it a lot. I thought, “What a great idea.” It’s a totally pretentious thing to say, but there’s a great quote by Stanislavsky about this: “Music is the most direct route to the human heart.” It’s really true. You can say with music what you could never say verbally to an actor.

Gray both wears headphones and has the music broadcast on the set, depending on whether the scene being filmed has dialogue or not. On Little Odessa, much directing was done to Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt suites. On The Yards, Bellini’s Norma (1831) and Verdi’s Attila (1846), Bach and Wagner, Ravel and Debussy, Mascagni and of course Puccini. Gray’s original script for The Yards has the film starting to the prelude of La traviata, and attempts were made to incorporate opera into the score in whatever way possible: at first using the music itself, then adapting it into the score. The story behind the journey to the final score is a fascinating one:

Gray: My original plan—which actually I could do now, but I couldn’t do at the time—was to rerecord large sections of Puccini’s verismo operas, but omitting the vocal score. So I would have the music from Manon lescaut, La bohème, and all this stuff, and it would play as score, and people looked at me like I was insane, because you know it sounds very highbrow, but if you actually listen to the music in the operas, it basically sounds like the greatest movie music ever. So, now you can do it. There’s a website and you can hire an orchestra in eastern Europe via ISDN line, you can record a whole orchestra doing what you want.... We couldn’t do this in 2000. So that idea was stricken down completely because it was financially unfeasible, it was like $500,000 before I shot a foot of film, it was insane. So, I was playing all this opera on set for the actors, and when we finally finished the picture what I had wanted was a kind of very classical style score, in which there was one or two key melodies which were repeated throughout the film in varying orchestration. ... So I had to try and find a composer who understood that this was a tradition of scoring.

The composer that Gray hired for the job was Jerry Goldsmith, whose work on Chinatown (1974) Gray had been a huge fan of. Goldsmith loved the movie and wrote a score, but Gray felt it was Chinatown all over again and therefore something he couldn’t use. Next Gray tried to use classical music itself, but it wasn’t working well because of how ferociously one had to edit the picture to get it to play well with music of that kind. Then:

I met with Howard Shore, who immediately understood what I was talking about... and we watched a temp that I did using Gustav Holst’s The Planets which I had used while shooting, I had shot the scenes to that. And he said.... that works great, why don’t you just use that, we’ll use that and I’ll write a couple other things but you should use the Holst..... He ended up writing about 25 minutes of music and I played him extensively Puccini and it was really turn of the last century stuff—the reason for that being I had wanted the movie to play like this verismo tradition, kind of social realist drama....—and he came up with stuff....

When [Shore] was done, he played the entire score for me on piano and harp, and we talked through each piece together. I would tell him to take a certain melody and expand it, because what I basically wanted was for two themes to be repeated throughout the film. I did the same thing for We Own the Night.

Shore: Opera is something that we both enjoy, and James was listening to a lot of Verdi and Puccini at the time. He was also very into the Saturn movement from Gustav Holst’s The Planets, in a version performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra. So the idea was to give the score for The Yards an operatic intensity, and to create a strong relationship between that music and the characters.

Holst’s “Saturn”, from The Planets, became the main mood piece structuring the music of the film, and beyond a nearly exact transcription (minus a few instruments here and there) of “Saturn”, Shore’s score also lifted from Maurice Ravel’s ballet music and aria derivations from Puccini’s operas. Before any composers were hired, Gray mourned for the fact that Nino Rota, composer for Visconti and The Godfather films, was a little bit unavailable (he’d been dead for twenty years). But once Shore was on board, they used Rota’s score for Rocco and His Brothers, as well as George de la Rue’s for The Conformist, as models to work from.

At some point in this whole process (at what point is unclear), Gray had reached out to his former Latin teacher Christopher Spelman, who was also a musician, in an attempt to explore the idea of doing classical guitar arrangements of Puccini arias for the film. I’ll simply drop here some rare words from Spelman giving context:

Spelman: [We kept in touch] really

throughout the time he was at USC—not super frequently, but we never lost

touch. Then he ended up making his first film Little Odessa while my

wife and I and our second child were living in North Carolina where I was going

to Duke. So we weren’t in the city while he was making his first movie, but he

called me up when it was released to make sure that I would go see it, which of

course I was eager to do. And then after we saw it, and thought it was really

great, he and I began to talk a bit more frequently and we talked about music

for film, and eventually when he was getting ready to make his next film... he

had the idea of seeing whether it would make since for a particular scene in

the next film The Yards for there to be a piece by Puccini or something

like that, a simple melody played in the style of a lullaby. And he wondered

whether it would sound good on guitar and he asked me to do a version. And I

did a version, but at that point I didn’t own a classical guitar, and it didn’t

sound that good. But eventually—I can’t remember really what the process

was—but I think it was probably he who said, well, maybe you should like record

it on a classical guitar and it would sound better. So I worked up arrangements

of about, I don’t know, fifteen pieces or so and recorded them in New York. By

that time we had moved back to New York. And they didn’t end up making it into

the movie, but in the course of preparing music for that movie he and I had

many, many discussions; we talked about opera, I started listening to more and

more opera. And that really is where the germ of our ongoing professional

collaboration started from.

__

One of the greatest disservices done to The Yards by critics over the years has been to label it a Godfather knock-off—about one of the most reductive things you could say. Nobody’s pretending that The Godfather films aren’t important to Gray (indeed, Godfather parts I and II were among the films Gray and his crew watched before shooting, along with Rocco and His Brothers, La bête humaine, The Conformist, The French Connection, and On the Waterfront); but to stop there is to give up on engaging with the film on its own terms. To ask Gray, “the story of The Godfather has nothing to do with The Yards at all. It just looks like it, and also has James Caan sitting in a dark wood room.” The Yards borrows the famous toplighting technique from Gordon Willis, but it’s a technique that really comes from painting, which Willis admittedly borrowed himself from Edward Hopper (who, in turn, borrowed it from painter Thomas Eakins—so you see, the influence game is never so simple as it seems....)

Gray’s partner-in-crime for creating the look of the film was Harris Savides, a music video and commercial cinematographer starting in the early ‘90s who would of course go on to shoot for many notable filmmakers (Fincher, S. Coppola, Baumbach, Van Sant, etc.) before his untimely death in 2012 at the age of 55. Savides contacted Gray out of the blue after seeing and loving Little Odessa on the recommendation of some friends of his, and he got his agent to set up a meeting with Gray in Los Angeles. Savides also came highly recommended from two friends of Gray’s: Mark Romanek and David Fincher, whom Savides had worked with before. They wound up getting along fantastically, and the results are on the screen.

Surprisingly, the two didn’t really talk movies. Gray sent him the script along with a tape of opera music to listen to while reading it, along with 40 watercolor storyboards he had painted, like he’d done on Little Odessa with Tom Richmond.[4] They took a trip to both the Met and the Whitney art museums in New York and talked about what they liked re: lighting and the direction of light, looking at a lot of renaissance works like those of George de la Tour and Rembrandt, plus Edward Hopper, who Gray attests that many filmmakers find something cinematic in. More words from Gray predict the look of The Yards: “All those painters had an obsession with a certain color scheme—no blues, but a series of browns, yellow ochres and buttery yellows, but also the way that they used light.” Add in the French realist painters of the 19th century while you’re at it, and mention must also be made of a Caravaggio influence—in the use of non-black blacks, but one could also find something of value in comparing the way Caravaggio used working-class people as his models for religious figures to Gray’s verismo desire to give working class characters the royal treatment.

Gray: It was an ambition with the movie to make it look like a series of paintings, to look almost seductively beautiful. It was like that line spoken by Burt Lancaster in Visconti's The Leopard—"the voluptuousness of death." There were to be no blacks—the moving equivalent of a painting by Caravaggio.

Savides: Georges de la Tour... uses

a candle most of the time. And for lack of a better way to describe it, there's

a kind of muddiness in the black, which is basically the fall-off of the lit

part from the candle to the blackness. It's not a true black. And true black

doesn't exist, really, in the world, nor does it exist in painting at all.

__

On the 2005 DVD release of the director’s cut of The Yards, there’s

included a list of twenty paintings that Gray cites as inspirations on the

film. I reproduce that list here for your convenience:

Railroad Sunset

Edward Hopper, 1929

Eleven A.M.

Edward Hopper, 1926

The Third of May 1808

Francisco Goya, 1814

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas

Caravaggio, c. 1602

Magdalene at a Mirror

Georges da La Tour, c. 1640

Magdalene with the Smoking Flame

Georges de La Tour, c. 1645

Saint Peter Repentant

Georges de La Tour, 1645

The Ecstasy of Saint Francis

Georges de La Tour, c. 1645

Saint Joseph, the Carpenter

Georges de La Tour, c. 1640

The Dream of Saint Joseph

Georges de La Tour, c. 1645

A Girl Blowing on a Brazier

Georges de La Tour, c. 1648

Boy Blowing on a Charcoal Stick

Georges de La Tour, c. 1642

Drug Store

Edward Hopper, 1927

Room in New York

Edward Hopper, 1932

Approaching a City

Edward Hopper, 1946

Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, c. 1875

David and Goliath

Caravaggio, 1599

Jusepe de Ribera, 1632

Saint Andrew

Jusepe de Ribera, c. 1631

Archimedes

Jusepe de Ribera, 1630

__

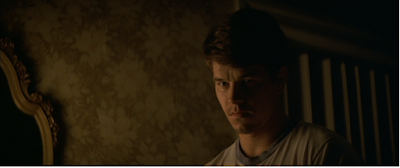

If there’s one name that should stay with you when thinking about the

look of The Yards it’s that of Georges de La Tour (1593-1652), a French

painter best known for his candlelit religious scenes, although his work was

all but forgotten until it was rediscovered in 1915. The opening chiaroscuro set

piece of The Yards is basically an excuse to play around with the hushed

beauty of candlelit interiors á la Georges de La Tour, the narrative contrivance

being that of a blackout halfway through Wahlberg’s “coming home” party.[5] The atmosphere of this

scene quietly extends its reach over the rest of the movie, and presents us

right out of the gate with all of The Yards’ power as a character study,

as a mood piece, and—let’s not beat around the bush—a moving-image masterpiece.

That “coming home” party, ostensibly a festive occasion, is really just another melancholic variation on the coming home party thrown for Robert De Niro—which he drives past unattended—in The Deer Hunter; Wahlberg’s return from prison (in for taking the sole rap on a grand theft auto without ratting out his friends) is cut through with the paradoxical air of the situation—loving family and friends are glad to have him back (his friends on the one hand with guilt for not having had to face prison time themselves, and his family on the other hand with disappointment for him having done the crime in the first place), but a wholly depressing bedroom meeting between Wahlberg and his parole officer dampens the proceedings even further while introducing the numbing and heartbreaking thread of the narrative, spoken by Wahlberg: “I just want to be a productive person again, you know, in society...” which he mumbles with a melancholy that would make mountains cry.

In just a few minutes, just about every theme in The Yards has been hinted at directly or indirectly, the tragedy perfectly set up, and all done organically by floating gracefully through a gathering á la the wedding sequence in The Godfather.[6] Relationships have all been delineated with an exquisite touch: we know immediately that Phoenix and Wahlberg are like brothers, and that the connection between Wahlberg and Theron is not strictly cousin-like and whose history is complicated by Theron’s soon-to-be engagement to Phoenix. We know that Wahlberg and Ellen Burstyn’s mother-son duo is unbreakable and loving, weighted by the absence of a father figure. We know that Burstyn’s sister Faye Dunaway has a new husband (Caan) that Theron isn’t thrilled about, and that he yet exists as a glint of hope for Wahlberg’s work prospects. That every one of these narrative building blocks is presented in tandem with and through the force of some of the most expressive and subtly emotional mise-en-scene I’ve ever laid eyes on completely evaporates any possibility of it feeling like perfunctory scene setting. (Having seen this film as many times as I have, as of my last viewing I can no longer entirely hold it together emotionally during this scene—the first real scene of the movie!—as the knowledge of what is to come, when paired with the impossibly beautiful strains of Gustav Holst’s “Saturn”, is just a bit too powerful for me. Taken entirely out of context, the first ten minutes of The Yards is maybe the greatest short film of all time.)

Gray: It was out of the question for me to make anything other than a social drama. My parents always thought in terms of class. I always felt in my father a deep disappointment of not being able to rise up through wealth. In the social context of America, one can always have the feeling of having coming close to the life one dreamed of.

When in the next scene Wahlberg goes to visit Caan looking for a job, entering the imposing edifice and then passing through the subway parts factory on his way to Caan’s office, we begin to get a glimpse of the larger social canvas against which The Yards will splay out. It’s the New York subway “as a metaphor for old-fashioned capitalism,” per Gray, an institution in miniature standing in for Institutions at large, an American system par excellence and therefore one that not so subtly has a lot to do with class and race. These two things being essential parts of Gray’s experience of growing up in America, as mentioned in the above quote—a quote which I cut off before the part where Gray says he feels lucky since most of the kids he attended school with are either dead or in prison. So The Yards is very much a story about the kind of people Gray knew growing up; for example, he’s said that Theron’s look in the film is explicitly based on a girl he went to school with.

(Another aspect which is a throwback to Gray’s youth is the film’s impossibly electric club scene; Gray himself was a frequenter of many New York City clubs in the 80s, and he captures the chaotic glory of the environment in a moment that is all the more amazing (and meaningful) for how radically it departs from the mood of the surrounding film. The almost feral entrance into the club was inspired by Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) of all things, and the moment where Charlize Theron gets tossed back and forth between Phoenix and Wahlberg was an idea taken from Mikhail Kalatazov’s I Am Cuba (1964). “I wanted the idea of the scene to be that this was a very sensate existence but also that she was gonna turn out to be a rather innocent victim in the scheme of things.” The fact that a parallel club scene, with its own bravura entrance and dance scene, also exists in Two Lovers shows Gray’s attachment to what these scenes represent, both phenomenologically and socially. He remarks that such scenes show “the social locus of urban life,” and by showing them he’s able to quickly and thrillingly paint a kind of urban cosmos.)

Wahlberg’s character is close to a living embodiment of the damage inflicted by America on its lower class urban youth via things like the penal system, social conditioning (“I just want to be a productive member of society” etc.), or the role of law enforcement. Our opening moments with Wahlberg on the train coming back home from prison—where he glances up at a cop standing a few yards away from him, in a simple shot / reverse shot / shot pattern—are a perfectly succinct demonstration in images via Wahlberg’s face just what the relationship between cops and someone like Wahlberg’s character is. To necessarily lessen the complexity of it by using words: a mixture of sadness and disgust in Wahlberg, coupled with the cop’s ignorance or indifference, in other words a relationship defined not by how one helps the other, but rather a history of conflict explicit and implicit where both have been unknowingly conditioned to keep the class system status quo, one for the other and one for himself, all adding up to a snapshot of a society where the threat of violence has long replaced any kind of true communal or neighbourly love. Or, as Gray puts it, it’s the idea that “implied violence is the central organizing principle of society.”

Gray told an interviewer that at the time he was making the film he was reading Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish (1975), a seminal text by Foucault on the history of punishment and the historical shift from the public site of torture to the private site of discipline, wherein the lawbreaker is encouraged to self-discipline via the secret threat of panoptic surveillance in a society where institutions exist to shape and mold bodies into prescribed functions of productiveness. Or, if you don’t want to get bogged down in theory, just return—once again—to the look on Wahlberg’s face and the sadness in his voice when he proclaims that he simply “wants to become a productive person” in society again. It’s the line and image that tells all. And to add to its heartfelt pathos, its titanic melancholia, one just has to recall that this was far from simply a character, or a role, that Wahlberg was playing. In 1988 at the age of sixteen Wahlberg had himself been arrested for assaulting a Vietnamese-American man, spending 45 days in prison. I mention it not to relitigate a 30 year old sin but rather to add a real life burden of guilt and grief to Wahlberg’s presence in the film; there’s a reason Wahlberg campaigned so strongly for the role, for as Gray attests Wahlberg would say to him, “I know that guy. I know that guy.”—and he did, for in many ways he was that guy, and that fact colors his performance to such a profound degree that I wouldn’t hesitate to call it, absent all hyperbole, the greatest performance ever captured on film.[7]

__

I really like James Gray who has made two terrific films, Little Odessa and The Yards. The first film was found magnificent. The second was very poorly received at Cannes. Me, I find it even better, but Cannes has screwed up his career a bit. I believe in this young man. – Claude Chabrol, 2006

One of the less remarked upon cinematic forebears of Gray’s is Claude Chabrol, arguably the most classical of the core New Wave directors and the most content to work in a mainstream genre context while still remaining no one other than himself. Chabrol had seen Little Odessa at the 1994 Venice Film Festival and immediately became a major supporter, and after The Yards there was no question that this Gray character was a filmmaker after his own heart, an if not the major American talent. In 2010, Chabrol would select The Yards as his carte blanche pick to be shown amongst a retrospective of his own films at Cavaillon in the southwest of France, a film which he called “the best American film of the past decade.” It was during the 2000s that the two got to know each other. (Chabrol also knew Ric Menello, at this time a friend and consultant of Gray’s before they would go on to write two scripts together; Menello has done several DVD audio commentaries for Chabrol films.) Arriving in France one time, Gray was greeted with a surprise:

This young woman comes up to me at the airport in Nice, and she hands me a pack and she says, “My father, he wanted you to have this.”... I go to my hotel room and I pull something out of an envelope... it’s an original poster for a movie called Les bonnes femmes—and it’s signed, “To James Gray from his absolute fan, Claude Chabrol.” ... It was his daughter in the airport.

The last Gray film Chabrol was able to see before his death in 2010 was Two Lovers: “It’s not because it’s a Hitchcockian movie that I have to like it, but I like James Gray’s Two Lovers a lot. For the first time in my life, I almost cried when Joaquin Phoenix took the glove....”

In 2010, the French magazine Première brought Gray and Chabrol together for a meeting. I couldn’t get a hold of the issue, but they did publish some excerpts on their online site, which I’ve translated here:

A few months ago, James Gray was in Paris for several weeks at the request of Guillaume Canet. Claude Chabrol was returning from Le Croisic for a few days in his pied-à-terre. The opportunity was too good... For James Gray, “there is Chabrol, Fellini, Kurosawa, Visconti, John Ford.” It is said. In tribute to the filmmaker who died this weekend, Premiere.fr puts online some extracts from the joint interview of the two directors, whose comments were collected by Stéphane Lamome for the magazine.

From this exchange emerges first of all a mutual respect, Chabrol proving to be as impressed with James Gray’s work (Little Odessa, Two Lovers) as the American director is with his senior. “James is an auteur like America no longer produces. We share the same cinephilia, we like the old-timers. He doesn’t realize that he impresses me as much as he is wrong to be impressed with me!”

Another striking aspect of this interview, Claude Chabrol did not mince his words. Very critical towards certain of his own films, he did not hesitate to defend what he liked in the industry of cinema, but neither did he hesitate to openly criticize what didn’t suit him. During his meeting with Gray, it was the supposedly prestigious festivals which got a proper dressing-down, as well as the ceremonies recognizing the best of the seventh art. “I have sympathy for neither Cannes, the Césars, nor the Oscars, I find that incredibly childish. I prefer the little festivals where you drink good wine.”

However, in 50 years of career, the director of The Beast Must Die [1969] has received some of these recognitions, including recent tributes honoring his whole career (the prix René-Clair in 2005, the Caméra d’Or in 2009 at the Berlinale...). But in reading James Gray’s words of praise regarding his films, he who was so struck by Les bonnes femmes, and the reactions of the person concerned, we realize that the most beautiful rewards he got came by branding the audience. To such a point that when Gray confesses to having stolen a few scenes from him to inspire passages in his own films, Chabrol is amused, and takes the opportunity to bring his failures up again, including certain feature films that he qualifies as “terrible shit.” Difficult to be clearer!

And here’s a six-minute video of Gray talking about Chabrol for ARTE TV.

And finally, Gray was asked to write the preface to Michel Pascal’s book Claude Chabrol (2012), which I’ve tracked down and translated here for the fun of it:

Claude Chabrol should have become a pharmacist. Both his father and his grandfather practiced this profession in Paris and in the bucolic village of Sardent, and he himself had gone to school for pharmacy after having studied literature at the Sorbonne. But at some point things changed, and he succeeded in escaping his destiny.

Unless, on the contrary, he has wholly assumed it.

He caught the cinema bug very young, and that can be a curse as much as a gift. Many of those who have contracted this virus often have to fight to expand their horizons beyond the dreamlike power of the seventh art. But not Chabrol. Anyone who has met him will tell you that he had a wider vision of the world thanks to a thorough knowledge of history and an acute understanding of the social classes and their influence on human behavior.

I myself had the opportunity to get to know him a little. As soon as I had seen Les bonnes femmes (was I really thirteen years old?), I admired him from afar. He was a legend, an immortal of the big screen. But paradoxically, this figure took on even more imposing proportions in my eyes when we finally met many years later. While writing these lines, I find myself wondering: how to find the right words, the ideal paragraph, to describe him? His spirit merits all possible eloquence, and yet in many respects he was literally indescribable. He represented the best in us, at once generous, friendly, brimming with vitality, mindful, irreverent, ironic, modest—and full of contradictions.

Of course, his films reflect his complexity. They are dark, but also supremely funny. They are distanced without being cold, extremely tense but without any haste. Intellectually rigorous and at the same time totally devoid of pretention. But above all, they show that he never stopped growing. In his early days, he established himself as the scourge of the bourgeoisie, denouncing its betrayals, its crimes, under an exquisite veneer, before becoming its tragic poet. This was Chabrol, conscious of the fact that he had to change in order to remain himself. He was so full of life... until life left him.

I learned of his death by the most impersonal medium possible: an e-mail. It appeared so proper, so grotesquely dignified. Chabrol himself would have laughed at such formality. Yes, the news of his death was sad, but it wasn’t tragic. He had led a full life, extraordinarily rich. Rightly acknowledged as a man of great talent, he was likewise much loved.

And for all of these reasons, his death hit me in an unexpected way. It took me several weeks to realize that my grief was totally selfish.

Selfish because I could no longer always see “the latest Chabrol.” Selfish because I could no longer show him my films. Selfish because I could no longer share a meal with him while drinking wine and discussing the world of art and politics. Selfish because I could no longer directly enjoy his caustic mind and his marvelous wisdom.

Also, in order to refresh my memories and to gather all the courage necessary for writing this preface, I watched Les bonnes femmes for the umpteenth time last night. From the beginning of the film, the man seemed to me more present than ever. The film spoke with such a clarity that it was as though Chabrol stood with me in the room. And I felt comforted, because in this way...

... Claude Chabrol essentially was and will always remain alive.

James Gray

August 14, 2012

__

Oh stars, oh faithful stars! When will you decide to give me a less fleeting appointment far from everything, in your realm of perennial certainty? – The Leopard (1963)

To say that James Gray films are about class is like saying the sky is blue. But I’d argue no film of Gray’s so explicitly finds itself concerned with the structuring of society along the lines of class as The Yards. When Wahlberg goes looking for a job at Caan’s subway parts factory class rears its head right away—Caan would like to help him, and says once he gets some schooling he’d have a job for him; but Wahlberg needs to work right now to start providing for his mother, who’s been refusing on principle any financial assistance offered by her sister and her new husband. Invited for dinner, Wahlberg and Burstyn make their way to Caan’s swanky mansion in Jamaica Estates, the upper-middle-class neighborhood in Queens just a few miles south of where Gray grew up. The film continues along these lines, and it's Wahlberg’s envy of Phoenix’s financial comfort from his role as a kind of money man for Caan’s company that eventually leads to his trouble, when things go south during a nighttime operation to take out the competitor’s trains.

Gray is no ideologue, but a Marxist reading of The Yards wouldn’t be unfruitful. Gray admits as much: “My films don’t defend an ideology, but they are Marxist in their historical analysis. In that domain, Marx is untouchable. His solutions were absurd but he had the workings of the world all figured out.” Take the idea of looking at the world through the history of class conflict—and then narrow it down to a single person (or, more broadly, a handful of people). This is what The Yards more or less does, and finds much of its dramatics via the way the individuals in it dream of either changing or keeping their class statuses. And through the film’s art and drama, it also fixes a common criticism of Marxism in that it zeros in on individuals, their emotions, their dreams, instead of losing the individual in a faceless sea of “the masses.” The “science” of analyzing material forces gets a makeover by Gray’s simultaneous and overriding deployment of the “art” of examining individual souls. Not just what is done to him, materially, but what it does to him, internally, is the question—the pressure of conformity, and combating the loneliness that comes with trying to fit into a larger system.

So it becomes a film about what Gray calls the “pathos of the outer boroughs,” where the view is from the outside looking in; remember, this is the same theme Gray presents us from his childhood, looking out of his bedroom window in Queens at the distant Manhattan skyline. Part of this pathos comes from the parallel pathos of what we might simply call Change—the New York of Gray’s childhood was not the New York of Gray’s twenties, and through this change we begin to get a hint of the historical forces working behind and above the scenes of the lives of individuals, Gray’s or his characters’. We see this in returning to some of Gray’s comments on Rocco and His Brothers:

And one of the things that that film is about is of course about the migration of this family from the agrarian south to the industrial north, and in a sense the entire A-story, which is the two brothers fall in love with the same woman, is all a kind of metaphor for the destructive power of heavy industry to tear apart this family.... So I had seen The Yards very much as a story of the deindustrialization of New York, the end of heavy industry era because I started to see the signs of a real tech boom and that wealth when I wrote the script, which was in 1995. And I wanted to make it about the death of this guy James Caan... the death of his way of life... and how he had to stay alive by corruption....

Through this, Gray’s film participates in the depiction and detailing of the New York working class’s plight amidst both shifting times and the political corruption that often both accompanies and catalyzes it. One of Gray’s points of reference for this was Robert Moses, a famous New York public official who throughout the 20th century often used his unelected position as a planner of public infrastructure projects to harm the very citizens he was meant to be serving, as detailed in Robert Caro’s famous 1974 biography The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. “We talked about Robert Moses a lot while preparing the movie, especially in terms of production design. I was trying to capture a New York that doesn't exist anymore, and that, at the time, was on its way out. I kept calling it the clash between an Archie Bunker-type New York and a New York of small-time rich guys.” The film is steeped in the history of New York corruption, rooted in the idea of a city whose public face is much different than the one showed behind closed doors. The character of Arthur Mydanick (played note-perfect by singer Steve Lawrence[8]) is explicitly based on Donald Manes, the Queens borough president from 1971 to 1986 who committed suicide amidst a nationwide political corruption scandal.

But the corruption theme was even more personal for Gray—almost too personal. In 1991, Gray’s father Irwin, along with one of his partners at Envort-Gray, was indicted on 56 counts, charged with paying $500,000 in bribes to a Metro-North official (who committed suicide during the investigation) and with billing for undelivered parts. The judge determined that Irwin Gray wasn’t heavily involved in the crimes; in 1992, he copped to three counts, paid a $50,000 fine, and got a suspended sentence. “But,” according to Gray fils, “I don’t think we’ve recovered yet. I’ll look at him sitting in the living room, staring, and I’ll say, ‘Hey, Pop, what’s the matter?’ And he’ll focus slowly and say, ‘I could never get it to work.’ Career, life—I’m not sure.” The James Caan character and his electronic subway parts company is explicitly based on Irwin Gray and his company. Gray had given his father the script of the film (which of course he had a strong reaction to), but he essentially agreed to act as a technical advisor on the film.[9]

In the film, James Caan’s office is almost exactly like my dad’s. And the film’s atmosphere of impending downfall is ours, too. I went off to college in 1987, and two months later my mother was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and a few months after that the federal government began pursuing my father. For the next five years, it felt like someone was stepping on my chest.

The Gray family had certainly been through the ringer, and all one needs to do to get an idea of just how difficult the situation was is watch Gray’s first two movies, fictionalized though they be; as mentioned before, the autobiographical nature of them is as much emotional as literal, if not more so. All I can add is a few pieces of oral history that help round out the picture.

Irwin: James never seemed to be paying attention. But obviously he saw the kitchen-table conversations with my partners, he heard that our competitors were shoving rags down our cooling tubes at the yards, he knew that it was war. The James Caan character is a composite, but I see myself in him. I should have known—I knew—that corruption was going on, but I was a zombie at work because of James’s mother. The end of her life was such a horror. It must have torn James apart to see all this.

James: Well, [my father] says he loves [the films]. But you know, I think he likes some more than others; he had a lot of trouble, I think, with the second film that I made, a movie called The Yards, because it was essentially all about his business dealings. It was very autobiographical, that film. I think that he has trouble with them. They are very autobiographical in many respects. It’s funny because, you know, a lot of people have come up to me and said, well, “you’re doing these genre movies, and you’re stealing from other movies,” and I feel like, well, that’s probably true, we all steal from everything. But I must say that maybe it means that my own life is hackneyed from a seventies movie. Because I’ve stolen, mostly, from my dad’s life and from my brother’s and my own. So I think that my father is uncomfortable with a lot of the things in the films. He would never say that, by the way.... I mean, there’s a lot of stuff, particularly in my first film Little Odessa which is very directly autobiographical, and he does not acknowledge it at all. He’s blocked it out of his mind.

And the end of a New Yorker profile

from around the time of the film’s release: The director has invited his

father to screenings of The Yards in New York, to no avail. “I told James

I’ve been very busy,” Irwin Gray said. “The truth is I’m scared to see the

film.” He paused. “But I’ll go. I’ll see it, of course. He’s my son.”

__

I have very little trouble saying, and can really think of no reason not to say it, that The Yards possesses the greatest ensemble performance in the history of cinema. The atmosphere of the film (and therefore, one can assume, the set) appears to be so conducive to great performances that I daresay if even I had been cast in the film somehow a great performance would have been coaxed out of me. But beyond writing hyperboles that aren’t actually hyperbolic, it’s fascinating to look at the Yards’ ensemble as the exemplary film of generational clash in terms of acting—precipiced on the cusp of the new millennium, it was clear by this time that a new way of acting was emerging that differed from the previous generation. Of the post-Brando school of actors making their name in the ‘70s—here Caan, Burstyn, and Dunaway—most studied under the direct or indirect influence of the Konstantin Stanislavski school of acting by way of American teachers like Lee Strasberg, Stella Adler, and Sanford Meisner. In contrast, the new crop of talent that bloomed in the ‘90s—here Wahlberg, Phoenix, and Theron—was mostly untrained professionally. Throw them together on the same set, and you get a unique set of sparks.

But Gray, trying to make a kind of modern social realist movie, didn’t or couldn’t rely on an actor’s reputation from other movies—rather, he looked for “whether the actor has shown in other movies a level of total commitment, and also a certain emotional awareness—a depth, a sensitivity.” And yet those reputations, particularly for the older actors, couldn’t be completely ignored, for “each actor brings a different mythology.” Aura and archetype mattered, but when that was combined with a true emotional intelligence, the results could be stunning. Just witness James Caan, Godfather lore looming large, now in the role of the (wannabe) patriarch: he plays the role of the small man in big shoes pitch perfectly, his dogged determination to keep his company from trouble at all costs dampened by a hidden, hushed gentleness that belies a deeper and truer man beneath the tough guy façade; when it comes out—like in his one-on-one conversation with Phoenix about Wahlberg and Theron’s history—it comes out in a whisper, barely opening his mouth to speak, with a tight-lipped pathos.

It's as if Caan had absorbed something from Wahlberg’s

performance, which is itself a moving masterwork of mumbling—the disappointment

he has in himself, and the sadness-infused effort of trying to make a go of it

in the world, veritably drips off of every word that slowly tumbles out of his

mouth. Because of this, the rare moment of happiness, exasperation, or ferocity

strikes twice as forcefully. Wahlberg proves himself right: it’s the role he

was meant to play. Gray compares him and his “blue-collar earnestness” to the

working class pathos of a late 1940s John Garfield performance. Phoenix is a

whole ‘nother story. At a young age (he was just 23 during filming) and without

much to speak of in the way of actual craft yet, he was like lightning in a

bottle—incredible, magnetic lightning, but lightning nonetheless. Gray never

knew what he was going to get on any given take from him; his biggest problems

usually came on the simplest lines of exposition, which Gray would shoot dozens

and dozens of takes of until he made it interesting. Because of this

explosiveness, great but often uncontrollable, the finished film is apparently

full of scenes where Gray had his editor Jeff Ford splice together different

takes from the younger actors, whereas in the very same scene every shot of one

of the older actors is from the same take. This element forced Gray to change

his shooting style: he had planned to shoot the film in elaborate masters, as

he had done on Little Odessa, but the variability of the younger actors

made him do away with the idea. This will be a theme throughout Gray’s career:

shifting his shooting style, and therefore his mise-en-scène, to fit the actors

that he’s working with. Perhaps this is how he consistently gets some of the

best performances of cinema history on his screen. Asked about it, he prefers modesty:

“I am very bad at directing actors.” Clearly untrue, or perhaps he’s right, in

that he knows how to let them be themselves, and simply love them for it.[10]

__

The parallelism of the first and final shots of the film is almost unbearable—Wahlberg, sitting on the train, camera trained on his face as he bumps along on the tracks. The film is a circle going nowhere, ending where it began, this time not bringing him home from prison but shuttling him off into the world—a different kind of prison, the confinement less visible yet still palpable. This time Wahlberg is wearing a suit, presumably off to find a “respectable” job, fulfilling the wish of his mother—“you always looked good in a suit,” she had said, her desire for him to be one of the suits going into the city both a loving yet naïve motherly gesture, tragically ironic given that these suits are the same men whose corruption had instigated the very sufferings they were facing at the moment she said this. Look closely in the last shot and you’ll see Wahlberg on the verge of tears. It’s one of those moments in movies where the tears aren’t necessarily a result of anything specific, but rather caused by the accumulated weight of everything that’s occurred over the length of the movie (and because of the movie’s ability to conjure a world beyond its frames, also over the length of that character’s whole life....) But it’s not even tears, just the verge of them—the moment of dramatic catharsis has already happened (the exact moment, which never fails to wound me: when Faye Dunaway collapses upon hearing of her daughter’s death), and this is but a coda.[11] But as the film fades to black one is struck by just how much specific, termitic truth has been conveyed by the film over the last two hours.

The Yards, in another universe that lost 1970s movie rediscovered in

someone’s attic, is a kind of “anti-movie” by virtue of its refusal to be

anything other than a timeless object. It straddles cinematic and artistic

history, out-of-time while still existing on a continuum of artistic history:

from Puccini to Visconti to Coppola to Gray, or choose your preferred points of

reference. I could say, instead, that The Yards is what a film looks

like when you put Cassavetian acting inside a Fordian mise-en-scène. I could

say that it’s a continuation of the “destiny machine” of Fritz Lang carried to

Gray through the mediation of Claude Chabrol. I can say whatever I want: how

about, it’s a Greek tragedy inside of a Shakespearian drama, Phoenix killing

Theron in an Othellian rage, or that it’s a film about cousins in the vein of The

Godfather: Part III but instead of time and redemption the theme is Louis Althusser’s

concept of free will as ideological fiction. The Yards is a myth, a

fable. Contra Little Odessa, it’s “uncontaminated by ethnicity,” a

specific lack of specificity that sends it off into the realm of timeless

dramatic archetype. The story is out of a dashed-off 1930s Hollywood programmer:

a man gets out of prison and wants to go straight but gets pulled back in.

(Gray even stole a shot from Gregory La Cava’s pre-code masterpiece I

Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang [1932], the ending where Paul Muni backs

into the darkness replicated in Wahlberg disappearing into the black before

visiting his mother in the middle of the film.) There even exist hints by

association of less reputable cinematic Italian forebears: Tomas Milian’s

presence (playing the rival company’s leader Manny Sequiera) conjures his

history in ‘60s and ‘70s poliziotteschi films, as Tony Musante’s does

for giallo (star of Dario Argento’s The Bird with the Crystal Plumage

[1970], here playing one of Caan’s associates.[12]) And another part is

played by Victor Argo, a staple of Scorsese and Ferrara films, Gray’s fellow

New York City cineastes. It’s definitely A New York Movie—there are even cameo

appearances courtesy of Knicks guard Allan Houston and Mets first baseman Keith

Hernandez.[13]

So from out of the giant artistic and cultural swirl containing everything from

the Greeks to Hollywood Gray pulls a masterpiece out of his hat that,

remarkably, is still nothing more than what it is in itself. Which is still a

lot. Everything. It’s the platonic work of art, and yet also a dirty little

movie that is so termitically determined to conjure its cosmos the hard way

that it refuses to be categorized outside of the confines of one’s emotions

while in the trenches of viewing it.

Following the tenets of classical tragedy, The Yards is not strictly speaking a drama—in the latter, characters can alter the paths of their lives; in the former, characters are under the spell of forces outside of their control. Another reference point in dealing with fate is the noir genre, although here it’s more cosmic, Greek, than that hardboiled version. Gray has said that he intentionally made The Yards less of a tone poem than Little Odessa, instead focusing his concern on people above all. For this reason and others The Yards has a warmth to it largely absent from its predecessor, literally and figuratively. The film was shot in the dead of summer instead of winter, and there’s no character—as human as he still remains—as coldblooded as Roth’s in Little Odessa here. The idea of destiny is conjured here in more explicitly human terms; it’s the Americanization of the old Greek idea of fate: the inability to escape your lot in life, your background, your class—your inability to recreate yourself.

But these “themes” don’t actually exist. As with any movie, they

arise in the mind during and after watching. They have no material existence in

the movie. What you do have are people, faces. And the ones in The Yards contain

more pathos than any other movie I know of. A deep sadness, a deep melancholy;

the feelings and emotions of The Yards aren’t really conjured, so to

speak, as they simply exist on and underneath the surface of the film; as the

viewer, we simply swim in them. It’s the kind of movie that is so emotionally rich

and incisive that it once upon a time led some guy on Letterboxd (me) to write

that in this movie Gray doesn’t film bodies but souls.

__

It would take over two years from the time Gray finished making The Yards to its theatrical release. And when it did it was minimal: in October of 2000 the film was dropped unceremoniously in only 150 theatres, without television advertising of any sort. During those two years, Harvey Weinstein had soured on the project and became increasingly resistant to Gray’s ostensibly non-commercial vision. As chronicled in Peter Biskind’s book Down and Dirty Pictures: Miramax, Sundance, and the Rise of Independent Film (2004), throughout the ‘90s one can see Weinstein becoming progressively greedier for Oscar gold while becoming less and less interested in actually supporting the artistic visions of those whose movies he was producing and/or distributing.

Gray had finished his first cut of the film all the way back in September of 1998. But as it got closer to its final shape, Weinstein of course wanted to hold his patented audience test screenings. But everything about the situation was always going to be disadvantageous to the kind of movie that The Yards was; the screening was to be held at a mall in New Jersey, and free passes to attend the test screening were being handed to audiences streaming out of the Adam Sandler movie Big Daddy (1999); audiences were lured with the promise of a thrilling Mark Wahlberg-starring action movie. The survey scores weren’t to Weinstein’s liking, and thus began a 19-month long standoff between Miramax and Gray—they essentially shut down post-production and demanded that Gray recut the movie into a sub-90 minute thriller with an upbeat ending. As post-production prolonged, the $17 million budget lurched closer to $23 million; both sides wanted something from the other. Gray wanted money for reshoots to shore up some POV issues he was having in editing, and Weinstein wanted a new ending. In a May 1999 meeting, they compromised (Weinstein, with the power, of course coming out on top): Gray would get three days’ worth of reshoots, but in return he would have to not only shoot Weinstein’s new ending, but also agree to do another film for Miramax. When Gray later asked for another additional day of reshoots, another film was added to his contract. (Another reason Weinstein stopped supporting the film is that he had wanted Mark Wahlberg’s agreement that he’d do his next two movies for Miramax; but Wahlberg, seeing the kind of person he was and how he had treated Gray, wouldn’t go for it.) Miramax now had Gray’s future commitment on two movies that he owed them. In return, Gray finally had his movie—or rather that, plus the tacked on studio-imposed ending.

The final push that got Miramax to actually release the movie in theatres, however, was a little bit of prestige courtesy of the 2000 Cannes Film Festival. One of the film’s producers had sent it to the Cannes selection committee and president Gilles Jacob loved it, and he invited it to the festival. Not that it made much of a splash there; rather, it began Gray’s long yet far from universally admired run of films to premiere at Cannes. So the film was finally released stateside in October of 2000, although “released” in name only. Put out in only 150 theatres with no TV commercials and limited advertising, it disappeared shortly after, bringing in less than $1 million in US box office. It was slated to be a commercial failure by Miramax before it was ever was given a chance, and they basically made sure of it.

But The Yards, “failure” though it may have been in the majority of people’s eyes, stands firm for me in the highest annals of the history of art. Gray did everything he could to see his vision to its end, even staking his own money at times. The last shot of the director’s cut[14], after no more money was coming from Miramax, was paid for out of Gray’s own pocket—a shot stolen on a real train with minimal crew. Gray even paid the rest of Savides’ salary himself. Not even Harvey Scissorhands could prevent Gray from seeing his vision through: indeed, the imposed ending can hardly be said to affect the theatrical cut's impact whatsoever, so strong is Gray’s emotional philosophy present in the very atmosphere of every shot of the film. It really just comes off like any imposed ending from the Hays Code years, its presence only highlighting the uncomfortable truths that it’s trying to paper over. Matt Reeves attests to their attempt at subverting Weinstein’s imposition:

But we did everything we could to make that ending feel like it could be part of what we were doing, to make it our version.... James and I talked a lot about Travis Bickle, and about the loneliness of someone who wants to become like other people. The idea was to show how damaged Leo was, to watch him struggling to find a way into this world. Even during that final speech, he still doesn’t quite fit in.

“He still doesn’t quite fit in”—this could be said just as well about Gray himself. At the turn of the millennium, to say nothing of now, Gray was an anomaly, someone with not only the desire but the artistic wherewithal to actually make the kind of out-of-time movie tragedies that nobody was thinking about or expecting to see anymore. The film occupies a weird patch of territory in cinematic history—neither a ‘90s film or a 2000s film, neither a 20th century film or a 21st century film (having been shot in the former but released in the latter), it transcends time, or maybe exists buried underneath it. In a fateful parallel, the corruption dealt with in the movie was reflected again in the movie corruption that Gray had to deal with in post-production. Something about it feels bigger than cinema, but also less than it—just a small little movie that I just happened to watch and that just happened to mean the world to me. Personal parallels and the fact that it was the first Gray I watched (technically I had seen The Immigrant prior, but no memory of that viewing reveals itself to me) maybe play into why it’s always stuck around as usually my favorite Gray and my sometimes favorite movie. At least at one point Gray felt similarly: “... in some ways The Yards is my favorite of my movies, even though it's my least successful movie on every level: worst reviewed, worst box office, and the most difficult to cut together. Perhaps as a consequence, I like it the most.” The “unloved” quality to the movie certainly helps to make it a favorite, something always worth talking about and defending and bringing to people’s attention. “Failures” that mean the world to you always tend to be more interesting than “successes” that mean the world to you. But whatever it is, at the end of the day all I hear is the ambient sound of the train on the soundtrack, Mark Wahlberg’s face bumping along as he goes on with his life, the camera on his face, capturing something which no words can articulate. Perhaps what’s being articulated is nothing more complex than simply “the way things are.” Gray:

I think there’s a beauty in sadness,

an acknowledgement that this is the way things are. That’s a part of

life—that’s a part of life that’s worth exploring in art....

__

[1] A late film

and a great film for Pakula, his last. A “classical” filmmaker and in that

sense a proto-Gray, Pakula worked with Gordon Willis often, as he did on The

Devil’s Own—a collaboration which produced a neglected masterpiece that beyond

its careful and somber style is chock full of Grayian touches both thematic

(ethnic destinies: “It’s not an American story. It’s an Irish one.” / “We never

had a choice, you and me.”) and structural (the narrative ends without closure,

ambiguous but not vague.)

[2] Reeves is

also responsible for the television series Felicity (1998-2002) along

with co-creator J.J. Abrams, another friend of Gray’s. I would be willing to

bet a couple bucks that a season 1 character named Zach, present for five

episodes before his shameful departure, is at least in some respects a portrait

of film school-era James Gray: curly red hair, slightly nerdish, and an

aspiring filmmaker. An actual quote said by the character in the show: “It’s

really competitive, you know? Film school. But I get to use the 16mm equipment

and hang around some really pretentious people, which apparently builds

character.”

[3] For a

thorough and myth-busting account of post-war Italian neorealism, I highly

recommend Tag Gallagher’s invaluable The Adventures of Roberto Rossellini:

His Life and Films (1998). (Available for free in PDF form.)

[4] This would

be the last time Gray did this before abandoning the practice for the rest of

his career. He would later say: “I don’t believe in a vision. I think vision is

overrated. I think you have the ideas, and then it’s a collaborative process

where you attract talent and hope that they can go beyond what it is you have

in mind. They shouldn’t give you exactly what you want.” / “I think it’s an

exercise in futility to try and get your vision on the screen, because it’s

never going to happen. The only thing that you can do is try to make sure the

film looks beautiful, better than you had imagined, as it slips away from you.”

[5] Shades of

the summer New York City blackout of 1977, which is a small but essential part

of Gray’s NYC cosmology as we’ll see even more when reaching Ad Astra.

(The blackout is also connected to a passing mention—it’s announced on

television as “up next” after the news report on Wahlberg—of the 1968 Doris Day

comedy Where Were You When the Lights Went Out?, set in New York during

the northeast blackout of 1965.)

[6] Many of

Gray’s films follow this tradition of opening with large gathering scenes—this

scene in The Yards, We Own the Night’s dual police convention/night club

scenes, The Immigrant’s Ellis Island, The Lost City of Z’s military ball, etc.

[7] As regards Wahlberg’s role vis-à-vis his real past, The Yards foreshadows The Immigrant in being a film with a streak of redemption running through it, or the very real possibility of it at least. I find this moving, and a good antidote to the prevalent attitude which condemns people for their past mistakes without ever reflecting on one’s own, as if empathy (real love) was only a good thing to have for some people and not all. The Immigrant will tackle this idea head on, going further and further into this darkness until happening on a little concept called radical forgiveness. At the risk of sounding reductive, The Immigrant is Gray’s “cancel culture” movie, and I’m only mentioning it in a footnote here so as not to have to bring it up when we get to there.)

[8] Fighting against

Weinstein on most of Gray’s casting desires, in order to have his way on this

particular choice “Gray had to guarantee the studio his salary against the days

it would cost to reshoot the Lawrence scenes if they didn’t work out.”

[9] Ironically, the film most explicitly, autobiographically about Gray’s father is one in which, strictly speaking, no father exists. Perhaps this was the necessary distance required to make it.

[10] An anecdote

from Gray: “I remember once I was working with Ellen Burstyn, who’s a great

actress, the queen of The Method, and she was like, ‘you don’t know how to talk

to actors. Talk to Paul Mazursky—he knows how to talk to actors.’ Two years

later, I’m at a restaurant and I see Paul Mazursky, so I go up to him and say

that Ellen Burstyn says you know how to talk to actors. And he says ‘No, I just

let her do whatever she had to do and said cut, perfect.’ And I thought, oh—the

way to talk to actors is to tell them how great they are.”

[11] Another coda

of tears welling up but not exactly falling that is also the presentation of

a tragic return to normalcy: Heaven’s Gate (1980), which amazingly plays

the role of both coda and catharsis by utilizing David Mansfield’s

swelling score to wrench every last tear out of your body. Contrast this to The

Yards, which ends in ambient silence....